Taglines: The legend is alive.

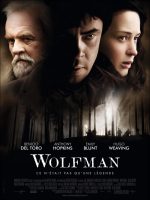

Inspired by the classic Universal film that launched a legacy of horror, “The Wolfman” brings the myth of a cursed man back to its iconic origins. Oscar winner Benicio Del Toro stars as Lawrence Talbot, a haunted nobleman lured back to his family estate after his brother vanishes. Reunited with his estranged father (Oscar winner Anthony Hopkins), Talbot sets out to find his brother…and discovers a horrifying destiny for himself.

Gwen tracks down Lawrence to help her find her missing love, his brother. He learns that something with strength and insatiable bloodlust has been killing the villagers. He tries to piece together the gory puzzle and hears about an ancient curse that turns the afflicted into werewolves when the moon is full. He hunts for the nightmarish beast and uncovers a primal side to himself.

Lawrence Talbot’s (Benicio Del Toro) childhood ended the night his mother died. After he left the sleepy Victorian hamlet of Blackmoor, he spent decades recovering and trying to forget. But when his brother’s fiancée, Gwen Conliffe (Emily Blunt), tracks him down to help find her missing love, Talbot returns home to join the search. He learns that something with brute strength and insatiable bloodlust has been killing the villagers, and that a suspicious Scotland Yard inspector named Aberline (Hugo Weaving) has come to investigate.

As Talbot pieces together the gory puzzle, he hears of an ancient curse that turns the afflicted into werewolves when the moon is full. Now, if he has any chance of ending the slaughter and protecting the woman he has grown to love, Talbot must destroy the vicious creature in the woods surrounding Blackmoor. But after he is bitten by the nightmarish beast, a simple man with a tortured past will uncover a primal side of himself…one he never imagined existed.

The Wolfman is directed by Joe Johnston (Jurassic Park III, Hidalgo) and produced by Scott Stuber (Couples Retreat, Role Models), Del Toro, Rick Yorn (The Aviator, Gangs of New York) and Sean Daniel (The Mummy franchise, Tombstone). The action-horror film is written by Andrew Kevin Walker (Sleepy Hollow, Se7en) and David Self (Road to Perdition, Thirteen Days), based on the motion picture screenplay by Curt Siodmak (1941’s The Wolf Man)

The Wolf Howls Again: Restoring a Classic

He has been given countless names by scores of cultures over thousands of years. There has long been a global fascination with the mythological creature known as the lycanthrope, a human with the unnatural ability to transform into a wolf-like creature when the moon is full. From the myths of the ancient Greeks to documentation by Gervase of Tilbury in 1212’s “Otia Imperialia,” horror stories about werewolves have dominated world cultures for centuries.

But it has only been in the past seven decades that the creature was committed to film. In 1935, Universal released Werewolf of London, from director Stuart Walker, but it was 1941’s classic The Wolf Man that firmly established the modern cinematic myth of the werewolf. The film created a lasting iconic character in the tragic figure of a wayward nobleman by the name of Lawrence Talbot, played by Lon Chaney, Jr., son of silent film icon Lon Chaney, star of The Phantom of the Opera and The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

Directed by George Waggner from an original screenplay by Curt Siodmak, The Wolf Man was Universal’s latest creature film in an era that spawned imagination and nightmares. The Talbot character went on to reappear in films for the studio including Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, House of Frankenstein, House of Dracula and Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein.

While the original, with its tagline of “His hideous howl a dirge of death!” became an instant classic, at only 70 minutes in run time, it was quite a short monster movie. It solidified the fame of star Lon Chaney, Jr. and included cameos from additional Universal “monsters,” including The Invisible Man’s Claude Rains as Sir John Talbot and Dracula’s Bela Lugosi as the gypsy who discovers the curse that’s been leveled upon Lawrence.

Actor / producer Benicio Del Toro has long been a fan of this genre and began to consider paying homage to the film with his manager and producer, Rick Yorn. Yorn explains his interest in beginning the project: “Growing up, these monster films really had an effect on my brothers and me. When I first came out to CityplaceHollywood, I wanted to remake one of the old movies. A few years ago, when Benicio and I were walking out of his house, I saw the one-sheet for The Wolf Man. It shows a close-up of Lon Chaney, Jr. as the monster. I looked at the poster, then back at Benicio-who had a full beard at the time-and said, `How would you feel about remaking The Wolf Man?’”

Del Toro was very interested in paying homage to the genre he’d loved since he was a boy. While he realized that would require him going deep into the makeup and prosthetics it would take to pull off the signature look of the creature, he was game for the challenge. “Frankenstein, Dracula, The Mummy…when I was a kid, I watched these movies,” Del Toro explains. “My earliest recollection of acting was watching Lon Chaney, Jr. play the Wolf Man. We wanted to honor this classic movie and the Henry Hull movie Werewolf of London. We knew it would be exciting to make it in the classic, handcrafted way.”

Del Toro didn’t want to remake the film frame by frame, but rather update it for modern audiences. He felt the story screenwriters Andrew Kevin Walker and David Self created “gave the movie some twists and turns and a modern edge, while still honoring the original story.”

Del Toro and Yorn set about getting the project off the ground and, during a dinner with producer Scott Stuber, the men decided it was time this classic was updated. “We have put in a few twists, but we wanted to honor the original,” says Stuber. “The Wolf Man is so iconic because, on some level, he is within us. Every person feels a sense of rage. Each of us feels a sense of that time when we went too far, got too angry, we shouldn’t have done. Something primal exists within all of us, and we must control it or we are doomed.”

It was never a doubt for the producer that Del Toro was perfect for the title character. Of the Oscar winner, Stuber commends: “Benicio’s got such powerful eyes. To feel so much emotion coming from under the transformation is critical to the heart of the movie. We didn’t want to separate the actor from the Wolfman…and end up having the beast here and Benicio there. The performance is always most important in order to feel for the character. The special affects are amazing, and they enhance the performance…they don’t create it.”

The three filmmakers were joined by producer Sean Daniel, who knew something about reinvigorating monster franchises himself; Daniel helped relaunch The Mummy series for Universal Pictures. Of his involvement in the production, Daniel notes: “It was really exciting to be asked to join in on giving new life to another of Universal’s great, classic monster characters that so inspired me when I was a kid.”

Together, the producers began the search for a director who could not only translate the drama of the script, but also execute a horror film that would seamlessly blend visual effects, creature effects and CGI.

When director Joe Johnston was brought on to the project, he took over the reigns from Mark Romanek, who departed during pre-production. An Academy Award-winning art director for Raiders of the Lost Ark, Johnston’s resume as a director includes a strong combination of character-driven films such as October Sky and epic visual effects movies including Jurassic Park III and Hidalgo.

As with all of his projects, the director was far more interested in story before spectacle. In screenwriters Walker and Self’s story, he found “underneath the action and the blood and the terror, a love story about Lawrence Talbot and his dead brother’s fiancée, Gwen. I wanted that relationship to be the element that held the story together…the key piece that invested the audience in understanding this horrible thing Lawrence is inflicted with.”

The former art director was excited by the visual challenges that would come from turning the script into an action-horror film: “I want to show the audience something they haven’t seen before in our process of turning a man into a werewolf,” notes Johnston. “We’ve all seen these transformations in werewolf movies, and they all rely more or less on the same visual elements. It’s stretching bones and hair growing on the face.

“We’ve done transformations in The Wolfman that you could only do with the help of computer-generated animation,” he continues. “We have a great place to start the transformation, which is Benicio Del Toro, and we have a great place to end up, which is Rick Baker’s makeup. But it’s not a straight-line transformation…we go off in multiple directions to get to the end result.”

The filmmakers knew that in order to deliver the spectacular sequences, they needed to find the perfect balance between practical effects and special effects. That challenge would be one of many throughout the course of shooting and editing the film. But before any of that could begin, it was time to cast the supporting players to help Del Toro bring the infamous creature to life once again.

Noblemen: Detectives and Young Victorians

As with other facets of The Wolfman, it was important for the filmmakers to include classic characters from the original horror movie. While Lawrence’s father-played by Claude Rains in the 1941 version-only had a very minor role in that film, the team felt that key relationship should be a large part of the 2010 update. In addition to Lawrence Talbot and his father John, they wanted to make sure they included characters such as Gwen Conliffe, the conflicted object of Lawrence’s affections, and Maleva, the chieftainess of the gypsies.

Producer Stuber summarizes the group’s thoughts on the stellar cast: “Benicio, Anthony, Emily and Hugo together bring tremendous depth to the story and give life to the spectacle and the horror elements.”

The younger Talbot not only comes back to Blackmoor to find out what happened to his beloved brother, he tries to reconnect with a father that abandoned him decades earlier. It is then that he is bitten by a werewolf and must deal with the realization that he will become a monster himself. The original story was expanded to create new layers of interaction between the characters, and that began with fleshing out Sir John Talbot.

Cast opposite Del Toro as Lawrence’s eccentric father was legendary actor Sir Anthony Hopkins. As the two Talbots have not seen one another or spoken for years, from the moment they reconnect, the relationship between the two men is naturally tense. For Del Toro, it was not difficult to slip into that part of the role, as he was initially nervous to work with the performer. He laughs: “At first, I was more in awe working with him than enjoying it. By just watching him, he helped me and gave me notes here and there. It was nice to have another actor give you suggestions. He’s a straight shooter; he’s done in two takes and was great to work with.”

Hopkins believed he had to tap into a place of dark abandon to be able to play Sir John. He explains the relationship between the two men: “It is one of coldness and abandonment. Lawrence has never been able to know his father, as he was sent away because of some unspeakable horror he witnessed as a child: the horror of his mother’s death. Sir John pushed him away and sent him to live in America, but he comes back to England as a world famous actor and discovers his brother is in trouble.”

Discussing his attraction to the role, Hopkins offers: “Psychologically, people enjoy looking at the dark side of life. Transformation, resurrection, salvation…this story has it all.” The performer was interested in how the relationship between these two men developed. He reflects: “Sir John is ice-cold and doesn’t express any gentleness with tragedy or grief; that’s just the way he deals with his son. He manipulates and needles him by offhand remarks, which are never overtly cruel, something suggested.”

Sir John, with his dirty nails, filthy clothes and unkempt hair, walks about a huge house that has become derelict. As well, he makes sure that Lawrence never knows where he stands in their relationship. Johnston enjoyed developing Sir John’s madness and nudging the friction between the two as soon as they reunite.

The director reflects: “Sir John is completely and utterly mad, but he embraces his own madness as if it’s the most normal thing in the world. Anthony has played parts like this in the past, but in The Wolfman, we don’t know he’s insane until halfway through the film. Up to that point, Anthony gives us these little glimpses into the madness of Sir John, and then the window closes and you wait for it to open again. He makes you watch to see what he’s going to do next.”

Hopkins commends of his director: “Joe is successful, he’s amenable, he’s pleasant and absolutely everybody can talk to him. He made it very easy for everyone, and that’s tough considering how much he’s had on his plate. He came in with little preparation and had to take on an elephant of a film, and there has not been a hair out of place.”

Selected to portray the tragically-in-love Gwen Conliffe-a role originated by the timeless Evelyn Ankers-was performer Emily Blunt. Since her breakthrough role as the sharp-tongued first assistant to Meryl Streep’s lead in The Devil Wears Prada, Blunt has developed a body of work loved by critics and audiences alike.

As Gwen, she plays the fiancée of Lawrence’s dead brother, Ben, and has come to London to beg her soon-to-be brother-in-law to help find her betrothed. As they discover Ben’s death, she begins to fall for Lawrence during the course of his stay in Blackmoor. Offers her director of her talents: “Just by using her face, Emily can tell entire stories without saying a word. Whenever we found a line that we could lose, we did. Emily so powerfully tells Gwen’s story with emotion…not just words.”

Remarking on her reasons for joining the film, Blunt says: “I was drawn to the role because of who was attached to it, and I found the script very moving. It wasn’t just about violence; there was a love story and a human struggle that I was attracted to. What’s beautiful about The Wolfman is that it’s a haunting story, but it’s also a love story. Joe started off with a vision of making a classic, sweeping, huge monster movie, and he has maintained that vision throughout the shoot.”

While she did not have to endure the laborious hours in the makeup chair that was required of others in the cast, Blunt could relate deeply to the creature…and Gwen’s feelings for it. She agrees with Hopkins, noting, “I think we desire that loss of control and the ability to change or to understand the dark side in us. There’s something very basic about the way animals attack, but there’s thought and malice behind what humans are capable of doing to each other that is even more frightening.”

Gwen soon realizes that Lawrence has a dark side and a wildness that she has never encountered in her past; there’s a danger present in him that she recognizes is buried within herself. Blunt sees Gwen as a “beacon of hope” because of her strength. She adds, “I like that in the face of adversity, as someone who has met a whirlwind of turmoil, fear and loss, Gwen has the ability to see the possibility for change. She’s very hopeful.”

The murder of Lawrence’s brother catches the attention of Scotland Yard’s Inspector Aberline, played by celebrated actor Hugo Weaving. Weaving’s character was based on the actual Inspector Frederick George Aberline, who was brought in to head the investigation of the Jack the Ripper murders after they were considered too much for London’s Whitechapel Criminal Investigation Department to handle.

Stuber discusses the production’s choice of Weaving as Aberline:“Hugo has a special intensity that is very believable. That is important in a monster movie, because the audience has to believe this myth is real. The more real it feels, the better and more horrific the story is.”

After he’d read the screenplay, the actor, who has made fascinating choices in his career, from The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert to The Matrix trilogy, was keen to take the role. He says: “It was a snap decision to play Aberline. I read the script and liked it, but I had to make my mind up there and then. It was a completely instinctive decision, but I really liked the material and thought Aberline was fascinating.

“Aberline’s a real character, but he has been given a slightly different interpretation by the writers and Joe,” continues Weaving. “He’s an intelligent man who obviously went through a lot during the investigation of the Ripper murders. He’s wise and canny and can be charming, but he’s also incredibly skeptical and doesn’t believe for a minute that anything but a man could be responsible for the murders in Blackmoor.”

With Lawrence under suspicion for the killings, Aberline travels to the hamlet to investigate further. He soon finds himself a true outsider amongst the locals. Weaving explains: “He’s in a situation where he comes to this tiny country village and they’re all talking about werewolves and demons; they lock their doors on a full moon. He’s a man from placeCityLondon who’s very no nonsense and doesn’t believe one iota in this rubbish.”

Until he eventually witnesses Lawrence’s transformation himself… Additional key players who bring the Talbots’ world to life include Nashville’s Geraldine Chaplin as Maleva, the gypsy who foreshadows the news of Lawrence’s curse; The Path to 9/11’s Art Malik as Sir John’s trusted manservant, Singh;Shakespeare in Love’s Anthony Sher as the insane asylum’s evil Dr. Hoenneger; and Valkyrie’s David Schofield as Blackmoor’s bedeviled Constable Nye.

Unleashing the Hellhound: Creature Design and Effects

Notorious for his design and transformation of David Naughton in John Landis’ classic An American Werewolf in London, six-time Academy Award-winning creature effects designer Rick Baker was asked to come aboard the production. He wanted to keep the look as close to the original Wolf Man as possible, while paying tribute to Jack Pierce’s creation from the ’40s. “Jack Pierce was my idol,” says Baker. “He was the guy I really admired, and I wanted to be true to what Jack did…but still modernize it. It’s still very much the Jack Pierce Wolf Man, but with a little Rick Baker thrown in. I wanted my Wolfman to be a little more savage and look like he could do a lot more damage than Lon Chaney, Jr.”

For producer Rick Yorn, the idea that Del Toro would be transformed by one of the greatest-living movie-makeup artists was simply a must. He notes: “Rick was our first choice; he’s a legend. You go to his shop and you see all the movies that he has worked on. It’s absolutely a museum. For us, he did such an amazing job.”

Academy Award nominee Dave Elsey, who co-created the look of the Wolfman with Baker, remembers the early days of preproduction as he and Baker were paying homage to the look of the fearsome creature. “The design brief we were given for the werewolf was very open, so we could almost come up with anything,” recalls Elsey. “We were sitting in Rick’s workshop, and the more we talked, the more it seemed like the best thing would be to create a fresh version of what people would recognize as the Wolfman. Rick brings so many ideas to the table and so much enthusiasm for this type of film; it’s a dream come true for us to be working on this classic creature.”

The producers and director Johnston were well aware that the sequences audiences most would anticipate in the film would be the transformation of the human protagonist into the title character. The Wolfman takes a leap forward in that department…with extensive help from the visual effects division, an area with which Johnston is intimately familiar.

Explains the director of the synergy: “The makeup is in several different pieces. It’s applied individually. It’s not a mask, so that allows Benicio to move and to express himself. We didn’t want to rely completely on computer animation, because you can break this barrier of believability or break the laws of physics. What we’re trying to do with these transformations is to keep it as absolutely real as possible and use VFX as a tool to extend what is possible with makeup.”

Baker tested the intricate makeup on himself before having Del Toro sit in his chair for the first time; it would be a process the men whittled down to three hours. Just to see what it would look and feel like from an actor’s perspective, Baker applied the hair with glue, airbrushed his face, poured “blood” in his mouth and took pictures of himself as the wolf. “It’s very different when you’re a makeup artist and you’re trying to get this guy ready and you know the clock is ticking so fast…it’s a blur,” offers the makeup artist. “But when you’re the guy in the chair, it’s a really different time frame.”

He adds that he’s much more familiar with his creations than the talent behind them. “I spend a lot of my time with actors in the face that I’ve designed for them,” says Baker. “They come in the morning as themselves and almost immediately I stick this piece of rubber on them, and I don’t see the actor anymore…but a creation. I recognize Benicio as the wolf; I hardly ever see him as himself.”

For Del Toro, Baker’s team created an “appliance” made of foam and latex that covered the actor’s brow and nose. The edges of Baker’s appliance were made quite thin, so that they would seamlessly blend into the actor’s skin when laid on top of his face. When Del Toro was fitted with a prosthetic chin, cragged dentures (complete with sharp canines), a real hair wig and a beard that was applied with bits of follicles glued to his face, he embodied the fearsome Wolfman.

Though the makeup application took hours, Del Toro was excited to be involved in the process. “As a kid, I always wanted to have those big teeth,” laughs the actor. “It doesn’t matter how long you’re sitting on that chair, with Rick the magic is bit-by-bit. You close your eyes for five minutes, you open them up again and something is happening. It was easy to go for it when you have such a great team of guys working with you and doing a terrific job.”

After Baker’s design had the production’s seal of approval, his creature effects team set about making the werewolf suit to match Del Toro’s new lupine visage. Originally, the werewolf was to be clothed, and Baker’s brief indicated that he wouldn’t need to overly dress the body. However, his four decades in movie makeup had taught him that, as the film developed, it might be otherwise. He comments: “We set about making a full-body hairy suit, a suit in which each hair is individually tied…a bit like a giant wig. But you can’t just make one suit, you need at least three for your principal actor and another three for any stunt doubles that need to climb rooftops or fight in real fires. That’s a lot of hair!”

The wolf suits were fashioned out of a preferred material of makeup artists, yak hair. Craftspeople traditionally use the coarse animal hair to mimic beards, moustaches or goatees. In keeping with the spirit of the production, Baker used this hair-the same material Jack Pierce used on Lon Chaney, Jr. in the original film-on Del Toro. Baker elaborates: “I also used a lot of crepe wool, which was cheaper for me to learn with when I started doing makeup at age 10. It’s much softer than yak hair, so we used crepe wool on some of the edges of Benicio’s facial hair; it blended into his face better.”

LOU ELSEY was chosen to be the creature effects department’s fabrication expert; in that capacity, she was responsible for every wolf suit the production needed. “There are so many different elements to creature effects and so many different departments that make up The Wolfman,” Elsey offers. “We had a fabrication department that worked on all of the body shapes so our Wolfman would have fully articulated muscles. On top of his muscles, we had a hair suit, which is a spandex suit worked to look just like flesh. We had sculpted elements on his chest and arms that had to be manufactured and painted.” She laughs: “There must be so many bald yaks in the world right now, we literally had to source it from everywhere we could.”

The creature effects team knew that the Wolfman would be doing some serious damage during production, so to add to his terrifying demeanor, his suit needed bone-crushing claws. Elsey adds: “We worked with Benicio to give him every bit of help we could so he could create his character. Even the way Benicio holds his hands with his claws is dynamic and brings the character to life.”

As Del Toro morphed from a quiet nobleman into a hound from hell, his facial features and body hair wouldn’t be the only things about him that would need to change. To give added height to the already tall actor, Baker’s team secured leg extensions that were based on artificial limb technology. A very simple, lightweight design, the new legs made Del Toro look even more towering and terrifying. The result of the attachments was werewolf leg extensions easy enough to wear for beauty shots. These appendages may also be seen in slow movement sequences, while other specially created feet were used for action sequences in which the wolf needed to jump, leap or run.

Chaney was so recognizable as the Wolf Man in the original film that Baker wanted his new design to allow the audience to recognize a good deal of Del Toro as the wolf. Elsey comments: “When you look at Benicio in his makeup, you can still see him in it, even with all the hair. Other werewolves are much more animal-like, but our character has a very human element to him. Benicio can do in makeup what a lot of people wouldn’t be able to do; he’s got a great face with very distinctive eyes.”

Del Toro committed wholeheartedly to the transformation, so much so the makeup team had a hard time maintaining Del Toro’s makeup after a few takes of him biting his victim and shaking his head around. They often found half of his prosthetic chin hanging off when he went for a retouch.

When it came time for the Wolfman to run, director Johnston and DP Johnson had to be imaginative with how they would capture the shots. Johnston explains: “We wanted that dogleg foot on the Wolfman. The feet that the stuntmen’s feet fit into were almost like high heels. The guys had to be suspended from overhead cables to enable them to run, jump or attack.” When necessary, Del Toro’s legs were replaced with CG legs.

Johnston concludes, “We use computer animation to allow the audience to see the Wolfman’s toes gripping the ground, pushing off the earth and flexing his legs…it really makes a difference in helping to believe the transformation is complete. The best visual effects are the ones that are invisible, that you don’t recognize as visual effects, or the ones that don’t draw attention to themselves.”

VFX supervisor Steve Begg’s team was charged with taking the effects of Rick Baker and expanding upon them as needed. When Johnston needed a jowl to unhinge or a brow to mutate, Begg brought Baker’s stunning practical effects to a whole new level. He explains: “One of the most overt effects in the film is the transformation into the werewolf. With our hybrid approach-with CG and prosthetics and makeup-we hope the audience won’t be able to figure out how each effect is achieved.”

The team appreciated the painstaking blending of the two schools. “The obvious route today is to go entirely CG, and there is a lot of CG,” says Begg. “But it’s not all the way through, and it’s nice to have a traditional-effects approach coupled with a high-tech approach. For example, in a scene in which Joe wanted the muzzle of the werewolf to expand a lot wider than it would normally, we put little tracking markers around the area we want to work on. We hope this blend looks effortless.”

London to Castle Coombe: Design and Locations

Due to the fact that the werewolf only rears his head late on a moonlit eve, a number of night shoots were required for the production. From the beginning, the filmmakers knew it would a long slog for the crew, who practically spent the first six weeks shrouded by waterproof tents as they donned their wet-weather gear.

One of the fundamental differences between the 1941 and the 2010 versions of the monster movie is the era in which it is set. The original stuck to its present day in Wales, while this film takes us back to Victorian England in the year 1890. The period of the film was chosen for many reasons. Foremost was the fact that a dirty, suspenseful, smoggy London lit by gas lamps and a foggy, sleepy hamlet would create a spooky atmosphere synonymous with a classic horror film.

As his crew designed the world that he and cinematographer Johnson shot, director Johnston had but one dictum for his team: “Make sure we’re all making the same film.” He explains: “My crew was all very conscious of what the period was and what it needed to look like. For the visuals, I wanted to give them a lot of flexibility and leeway to help me tell the story. I’m really happy with the way it looks: cold, gritty and bleak.”

Sleepy Hollow’s Academy Award-winning production designer Rick Heinrichs discusses his involvement in creating a period horror film: “Shooting in England was a wonderful experience and a challenge to get back the look and feel of Victorian London; the face of the city has changed so much over time. Unfortunately, World War II decimated London and quite a bit of the 19th century has been lost because of the bombing.” Heinrichs had to target certain areas of the city that still exist to give him a foundation to build upon-either through practical sets his team created or with the constant help of the visual effects divisions.

One of the designer’s most ambitious tasks was finding a location for the Talbot family manor. “It’s so important to the story, and it had to be very carefully selected,” says Heinrichs. “All of its characteristics needed to help the visual narrative of the story. In many horror films, the default choice of design would be a Gothic structure, but we wanted to avoid the clichéd scary-mansion look of many horror films and present the energy of the house itself through its design.”

After scouting throughout England, the crew found Chatsworth House in Derbyshire, which is currently owned and occupied by the duke and duchess of Devonshire. The house, or the “Palace of the Peak” as it is known, was first built in the 1500s, and Andrew Robert Buxton Cavendish is the 11th duke to reside on the magnificent grounds.

Chatsworth House provided multiple facades for the four different looks Heinrichs and Johnston wanted for the house. Fortunately, the duke and duchess allowed the art department to modify the exterior of the manor temporarily. This allowed the crew to “overgrow” the gardens and prepare the front of the house to give it the appearance of a desolate, unloved and unkempt residence to which no man would eagerly return.

Heinrichs elaborates on Johnston’s mandate to show duality throughout the picture: “The story we tell is about a man who is struggling with two sides of nature: the civilized side conditioned by society and the animal that lives within. We felt it would be a good idea to have these two natures represented visually in the family house. We started with a very clean, classic structure and we added grass and greens to make it look neglected and disused, as well as woolly-to represent the animal inside him.”

It was Heinrichs’ mission to design an environment that reflected how the Talbots live or, as he puts it, to “show the saint and the sinner.” Every exterior is battling against the interior of the home, and Heinrichs’ aim was to take the audience on a journey from order and civility to the wilder depths of the animal that is at the film’s heart. For example, the contrasts one can find in the combination of light stone and dark wood inside the house plays on the finishes and the reflectivity of light buried inside Talbot manor.

The locations department was responsible for finding the 13 major exteriors for the film that brought the world of The Wolfman to life. In addition to the physical locations they dressed, Heinrichs and his team had to design and assemble some 90 to 95 sets within a very tight schedule.

Heinrichs and Johnson’s approach to the film was to try to get as much on camera as possible and lend the visual effects departments all they needed to create parts they simply could not shoot, such as disguising the modern trappings found on every street the team came across. The crew found a bit of luck when it happened upon one of the easiest villages to disguise as a Victorian hamlet: Castle Coombe, which doubled as the town of Blackmoor.

A medieval town that has been around for almost 900 years, Castle Coombe has a number of structures that descend from earliest British architectural design. Many of the houses there are listed as ancient monuments, and the passage of time has made the buildings lean into each other beautifully. The production agreed it had a very wonderfully shopworn, antiquated feel to it. For the purposes of The Wolfman, Castle Coombe became a creepy village full of superstitious people who live in dark houses and reinforce one another’s eccentricity and irrational beliefs.

Once production agreed on the location, it was up to the location manager, Emma Pill, to persuade the local residents to agree to the shoot. Working closely with Heinrichs and the art department, Pill had to determine which trappings of the modern day could be removed or covered up for the duration of the production. From power cables and television aerials to alarm boxes and modern locks on front doors, anything that smacked of the 21st century had to go. The Royal Mail post boxes belong to the queen and could not be moved, so the art department created a clever disguise that could be removed when locals needed to post letters, and put back when the crew was set to shoot.

After Lawrence Talbot is sent to the asylum for the second time in his life, the Wolfman goes on a rampage throughout London. Finding a location big enough to stage a huge production proved a little tricky. The filmmakers decided on the Old Royal Naval College in Greenwich, a site planned by Sir Christopher Wren and completed by such architects as Nicholas Hawksmoor, Sir John Vanbrugh and James “Athenian” Stuart. Situated on the banks of the River Thames in London, the college was originally built as a hospital for the relief and support of seamen and their dependents. Eventually, it became a naval training center for officers from around the world.

Of the shoot, Heinrichs remembers: “It was a big challenge for the locations department to find areas of London that were pure enough for us to work with on a large scale. One of those places was Greenwich. Although it’s been used many times on various productions, we were able to adapt it to our purposes. Through some use of visual effects, we made it our own. We needed to have a wide open canvas in order to create a very large set piece for the action to occur.”

placeCityGreenwich not only provided the filmmakers access for the long preparation and shooting, but also allowed them two units that shot for eight nights-providing a controlled environment that was perfect for the nature of the stunt work.

Expanding the environmental visuals were, once again, the VFX team, led by VFX supervisor Begg. He reflects: “As the film has developed and grown, we’ve done a lot of environment work…like big vista views of London. We haven’t just handled the werewolf, we’ve added to the atmospherics and the various locations in which much of the action takes place.”

Adds VFX producer Karen Murphy: “There’s a huge amount of atmospherics and matte painting in this film. Hopefully, because it’s a period film, you’ll see a period character walking down the street at night and not realize how much we’ve removed.”

His Lonesome Howl: Cry of the Wolf

VFX, SFX, makeup, locations and schedules were nothing when compared to the biggest challenge of the production for director Johnston. The Wolfman’s toughest obstacle was one the reader might think would be minor: perfecting the haunting howl of the title creature. Johnston explains his conundrum: “When it came time to lay in the sound of the wolf howl, we tried everything from animal impersonators to a crying baby and artificial sounds. We took those sounds and digitally processed them…looking for just the right combination of things to give us the perfect howl. But we just could not find it. We wanted it to be iconic, but something audiences had never heard before.”

A breakthrough would come when one of the production’s sound designers came up with a unique idea. According to Johnston, “Howell Gibbens said, `What is the purest and most controllable vocal sound that you can find? It’s arguably an opera singer.’ So we auditioned a number of opera singers in Los Angeles and picked the perfect guy: a bass baritone opera singer.”

After Johnston and his sound team recorded about a dozen howls, they knew they’d found their perfect wolf howls. The director notes: “His howls go through a range of emotions…from angry and victorious to mourning. We pitched them down about 40 percent so they became truly terrifying. When we pitched them down, we had these haunting, visceral animal sounds. They sent chills up our spines and gave us exactly what we were looking for.”

Victorian Costumes: Milena Canonero’s Design

Triple Oscar-winning costume designer Milena Canonero, whose previous work includes her stunning costume work for Marie Antoinette, has an extensive background working on period films. Johnston asked Canonero to make the costumes for The Wolfman very gothic, which, in 1890, included strikingly angular shapes. She used dark, rich colors, which were unlike the light, frothy look that could be seen at the end of the 19th century in England.

A perfectionist in detail, Canonero wanted to make the division between the upper- and working-class characters in The Wolfman very apparent. The upper echelon’s costumes were comprised of sharp silhouettes and long elegant lines, with materials including silks, velvets and furs that were indicative of the characters’ social status. The working-class characters she designed for wore outfits that were bundled up; she dressed them in fabrics including wool, linen and cotton. The upper-class men were put in top hats and bowler hats, while the working-class men’s hats were given a more rough-and-ready, beaten-up look.

Most of the costumes for the principal cast were handmade and, due to the transformation and action scenes, some of the costumes were recrafted up to 20 times. Having multiple copies of many of the pieces proved very helpful, especially for scenes that included blood and fire (in which case the fabric was fire-guarded to protect the stunt double). For the larger crowd scenes, Canonero’s team dressed the background actors in clothing found in costume houses from France and Italy to throughout England.

Gwen Conliffe is in mourning throughout most of the film and, therefore, was dressed primarily in black. As a member of the upper crust, she was dressed in corsets mixed in different textures and shades of black. To add a bit of color, Canonero had her team find teal velvet fabric to mix in with the mourning fiancée’s dark sleeves and skirt. As Gwen eases out of her grief and finds unexpected romance with Lawrence, the team dressed Emily Blunt in lilacs and dark purples. Of the corsets, Blunt laughs: “It was all about the waist in that period, which means that my internal organs now hate me.”

Though Sir John Talbot is very much aristocracy, he has rarely left his decaying home in the past several decades and no longer takes care of his image. Inspired by an Edward Gorey illustration, Canonero’s team created Talbot Sr.’s clothing by using pieces that were once beautiful but now heavily worn; the result was the creation of decayed elegance. A former hunter who made dangerous excursions to placecountry-regionIndia, Sir John had numerous trophies and other eclectic souvenirs as part of his wardrobe, including furs that he wears with his dressing gown and overcoat.

Lawrence has returned to England from America; when he is reintroduced to the audience, he is the star of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Because his character has traveled back and forth across the Atlantic, Canonero’s team gave his costumes a look that is more expansive than a regular upper-class English gentleman’s.

For the transformation scenes in which the beast emerged, the team prepped Del Toro’s costumes so that his seams would expand and rip as his muscles grew. They used stretchy fabric and thread that could literally appear to burst and tear apart. As Del Toro often was dressed in costumes made of tweed, the team found stretchy nylon that matched that fabric on camera. The final piece of Lawrence Talbot’s wardrobe created for the film was the production’s favorite: an actual replica of the wolf-head cane grasped by Lon Chaney, Jr. in the 1941 film.

The Wolfman (2010)

Directed by: Joe Johnston

Starring: Benicio Del Toro, Anthony Hopkins, Emily Blunt, Hugo Weaving, Art Malik, Gemma Whelan, Simon Merrells, Nicholas Day, David Schofield, David Sterne, Jordan Coulson, Julie Eagleton

Screenplay by: Andrew Kevin Walker, David Self

Production Design by: Rick Heinrichs

Cinematography by: Shelly Johnson

Film Editing by: Walter Murch, Dennis Virkler, Mark Goldblatt

Costume Design by: Milena Canonero

Set Decoration by: John Bush, Vincent Jenkins

Art Direction by: John Dexter, Phil Harvey, Andy Nicholson

Music by: Danny Elfman

MPAA Rating: R for for bloody horror, violence and gore.

Distributed by: Universal Pictures

Release Date: February 12, 2010