Biutiful is a love story between a father and his children. This is the journey of Uxbal, a conflicted man who struggles to reconcile fatherhood, love, spirituality, crime, guilt and mortality amidst the dangerous underworld of modern Barcelona. His livelihood is earned out of bounds, his sacrifices for his children know no bounds. Like life itself, this is a circular tale that ends where it begins. As fate encircles him and thresholds are crossed, a dim, redemptive road brightens, illuminating the inheritances bestowed from father to child, and the paternal guiding hand that navigates life’s corridors, whether bright, bad – or biutiful.

After having globe-trotted with Babel, I thought I had explored enough multiple lines, fractured structures and crossing narratives. Each of the films I have made has been shot in a different language, in a different country. At the end of Babel, I was so exhausted I made it a point that my next film would be about just one character, with one point of view, in one single city, with a straight narrative line and in my own native language. Using a musical analogy, if Babel was an opera, Biutiful is a requiem… and here I am. Biutiful is all that I haven’t done: a linear story whose characters shape the narrative in an unexplored genre for me: the tragedy.

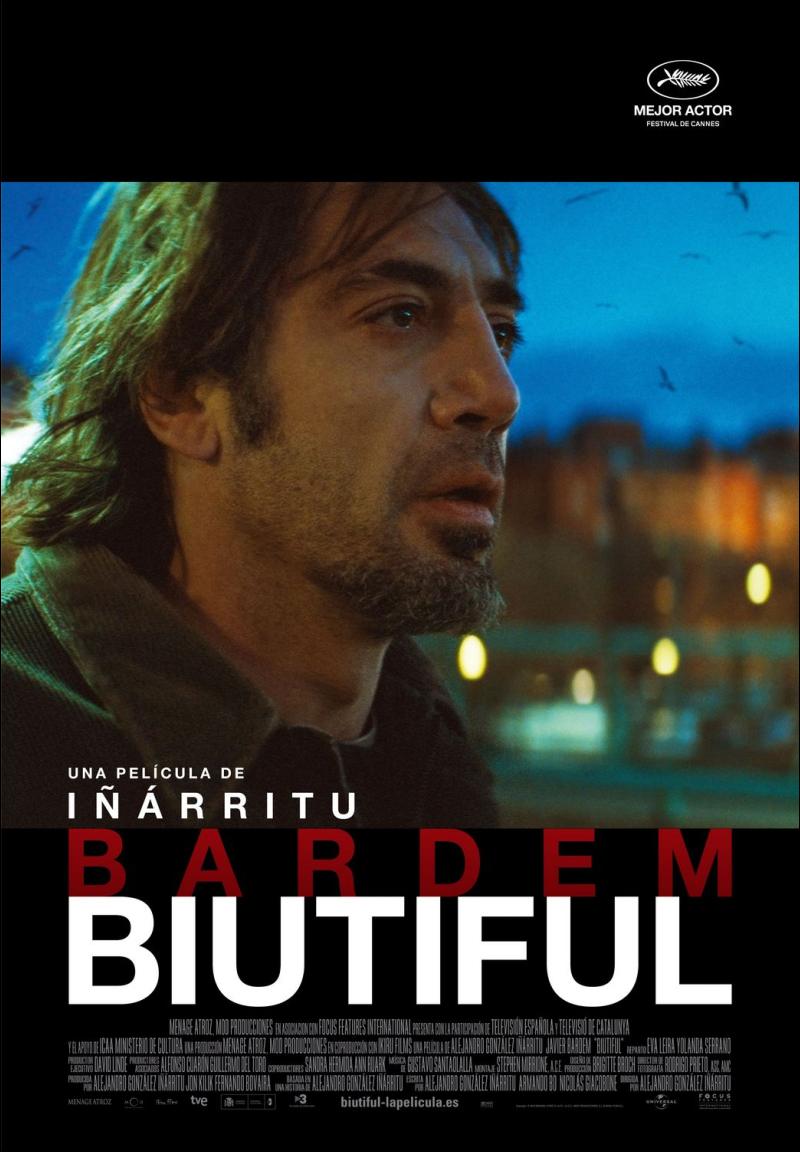

Biutiful is a Mexican-Spanish drama film directed by Alejandro González Iñárritu and starring Javier Bardem. It is González Iñárritu’s first feature since Babel and fourth overall, and his first film in his native Spanish language since his debut feature Amores perros. The title Biutiful refers to the phonological spelling in Spanish of the English word beautiful.

The film was nominated for two Academy Awards in 2011: Best Foreign Language Film and Best Actor for Javier Bardem. Bardem’s nomination makes his performance the first entirely Spanish-language performance to be nominated for that award. Bardem also received the Best Actor Award at Cannes for his work on the film.

Biutiful took three and a half years to make, since the beginning of the writing process. It was shot between October 2008 and February 2009 in Barcelona, Spain. It was a Mexican and Spanish co-production. The film was shot in chronological order by scenes.

On Biutiful by Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu

After having globe-trotted with Babel, I thought I had explored enough multiple lines, fractured structures and crossing narratives. Each of the films I have made has been shot in a different language, in a different country. At the end of Babel, I was so exhausted I made it a point that my next film would be about just one character, with one point of view, in one single city, with a straight narrative line and in my own native language. Using a musical analogy, if Babel was an opera, Biutiful is a requiem… and here I am. Biutiful is all that I haven’t done: a linear story whose characters shape the narrative in an unexplored genre for me: the tragedy.

Biutiful for me is a reflection akin to our brief and humble permanence in this life. Our existence, short-lived as the flicker of a star, only reveals to us its ineffable brevity once we are close to death. Recently, I thought of my own death. Where do we go and what do we transform into when we die? Into the memory of others. This is the anguishing and dizzying race against time that Uxbal faces.

What does a man do in his final days of life? Does he dedicate himself to living or to dying? Perhaps Kurosawa was right when he said our dreams of transcendence are just that: an illusion. Regardless, since the film’s inception, I was never interested in making a movie about death, but a reflection in and about life when our inevitable loss of it occurs.

Modern society suffers, among many things, from a profound thanatophobia. For this reason, I realize the formal and thematical contradiction of creating a sordid poem about an enlightened man while he is falling into the darkness of death and the unknown is a challenge. I say contradictory because while the internal spiral of Uxbal goes towards his interior and the spiritual, the urgency of this new social and political reality of Europe stretches his external spiral towards the opposite direction. The news reports statistics of hundreds of millions of people dying and exploited inside these human beehives that form in the suburbs of every European city.

The vertiginous and vacuousness of this news is difficult to metabolize. The hard reality of the poor, the immigrants, the ones who are always invisible. Upon visiting Barcelona in 2007, the character of Uxbal told me he belonged to this world. For me, individualizing only one of these realities was worth the trip. For many people, what appears to be an extreme reality, for the is only a natural part of their existences and the ordinary of their day to day. Many of the characters were played by non-actors and had lives parallel to the world of the film. But how did all this arise?

A film for me always begins with something very vague — a bit of a conversation, a glimpse of a scene through a car window, a shaft of light or some music notes. Biutiful started on a cold autumn morning in 2006 while my kids and I were preparing breakfast and I randomly played a CD of the Ravel Piano Concerto in G Major. Some months before, I had played the same Ravel piano concerto during a family car trip from Los Angeles to the Telluride Film Festival. The scenery of the Four Corners area was breathtaking but after the Ravel piece finished, both of my kids started to cry at the same time. The melancholic quality, the sense of sadness and beauty that this piece of music contains was overwhelming for them. My kids couldn’t take it or explain it. They just felt it.

When they heard that Ravel piano again that morning, they both asked me to stop the CD. They remembered very clearly the emotional impact and how that music moved them. That same morning, a character knocked on my head’s door and said: “Hola, my name is Uxbal.” During the next three years, I would spend my life with him. I didn’t know what he wanted, who he was or where he was going. He was dismissive and full of contradictions. But to be honest, I knew how I wanted to present him and how I wanted to finish with him. Yes, I just had the beginning and the end.

It wasn’t until one year later, while I was walking in the El Raval section of Barcelona, that everything made sense. Barcelona is the queen of Europe. She is indeed beautiful, but like every queen, she also has a much more interesting side than the obvious and sometimes boring, bourgeois beauty that every tourist and postcard photographer has admired. Since I was 17 years old and traveled around the world working in a cargo ship as a floor cleaner, I have been attracted to, curious about and fascinated by the neighborhoods that are hidden and that nobody sees.

That’s what I respond to. And I am talking about the diverse, complex, marginal and multiethnic new world that has been recently created in Barcelona and most of the big cities of Europe. It would have been impossible to imagine this when I first came to Barcelona at 17. But now, immediately, I knew that Uxbal belonged to this place, I knew he belonged to this eclectic and vibrant community that is reshaping the world.

During the 1960’s, Franco promoted and brought to Catalonia hundred of thousands of people from different parts of Spain, trying to disrupt the Catalan culture, and prohibited them from speaking the Catalan language. In the midst of a huge economic recession, the Castilian-speaking people — mostly from Extremadura, Andalucia and Murcia — became immigrants in their own country. They were assigned to a suburb of Barcelona called Santa Coloma and they became known as “Charnegos,” a derogatory word that refers to poor immigrants and their children.

With the returning strength of the economy during the 80’s and the 90’s, the “Charnegos” started leaving Santa Coloma and immigrants from all over the world started filling it. Even though El Raval, known as the Barrio Chino, is famous for being Barcelona’s most diverse neighborhood, it was Santa Coloma and nearby Badalona, that I fell in love with. Here, Senegalese, Chinese, Pakistanis, Gypsies, Romanians and Indonesians all live together in peace without a problem and each one speaks their own language without a need or worry of integrating into Spain. And to be frank, it seems the society is not very interested in integrating them either.

This is a neighborhood that has not been pasteurized. It is human, it smells and has texture and contradictions. It is a real example of “convivencia” – of community — and has the DNA of a perfect UN. The migrations and racial mixes that in the past took 300 years have been experienced here in just 25 years. Of course it’s not devoid of pain and tragedy. Every year, hundreds of African people die from drowning trying to get to the coast of Spain. The images are hard to watch. Also, almost every day you see in the newspapers articles about Chinese immigrants being abused or exploited all around Europe.

Just in the UK, there are one million Chinese people, as Hsiao-Hung Pai writes in Chinese Whispers: The True Story Behind Britain’s Hidden Army of Labor. Unlike in the US, the people don’t come to European cities to blend into a culture. The research I did tells me that most people come here in order to survive and to help the ones they left behind.

But more than this interesting sociological phenomenon happening in Barcelona and most European cities, it was the emotional impact it had on me that I found as a great context for the story of Biutiful. Although I am a privileged one, I am an immigrant and I have been for ten years. The immigrant conscience or geographical orphanage is a state of mind. In Biutiful, there are no grand occurrences. Only the individualization of the difficult every day life of one of the hundreds of millions of modern day slaves that live in this shadow and this light. At the end of the day, when a film is not a document, it is a dream. And as a dreamer, you are always alone, as a painter is alone with a white canvas. And to be alone is to ask questions (as Goddard once said )… and to make films is to answer them.

I wrote a meticulous biography of each one of the characters. I did it for the Chinese and the African characters, too. Each one should have a past and a reason and not only be utilitarian characters. I did this in order to know them well and also to help the actors understand where they had come from. Uxbal was born as a “Charnego” and he is one of the 10% Castilian-speaking people who stayed in Santa Coloma. The immigrants are not alien to him. He grew up with them. He works with them. Walking in that neighborhood on a Sunday is a physical, spiritual and emotional experience. You can see Gypsies singing in groups in the streets, while Muslims pray at the park or chant through the speaker of a little mosque, and a Catholic church is full of Chinese people. I wanted this story to be that same kind of physical, spiritual and emotional journey.

Since my visit to Barcelona, my subconscious started compulsively dictating the story. My daughter Maria Eladia told me that when an owl dies, it spits a hairball from her beak. I dreamt that night about that image. And then, everything started differently. I saw Uxbal full of contradictions: a guy whose life is so busy and complicated that he can’t even die in peace, a guy who protects immigrants from the law while he himself exploits their labor. A street man who has a spiritual gift and can speak with the dead and guide them to the light… but he charges money for it; a family man with a broken heart and two kids who he loves yet can’t help but lose his temper with them; a man who everybody depends on but who also depends on everyone; a primitive, simple, humble man with a deep supernatural insight.

A Sun surrounded by satellite planets. I saw him as a physical system in which the body is the street, the heart is the family and the soul is the search for an absent father. Before I started the script, I drew a map. I draw two spiral circles and a line that defined graphically Uxbal’s journey and his state of mind. One spiral moved from the inside to the outside. This was his everyday life out of control. The other spiral moved from the outside to the inside. This was Uxbal’s heart, going deep, into profound territory. And then I drew one line crossing the two spirals: the spirit.

My father used to say that low-income workers or taxi drivers can’t get depressed. “This is a luxury for the rich,” he said. Life will not allow them to die. And that’s Uxbal: a desperate, lonely man, looking for a father he never knew. After I had finished a first draft of the script, I decided to invite the writers Armando Bo and Nicolás Giacobone to the process. Writing is not an unknown process for me, but my experience has taught me that in writing a script, which is a very early and technical stage of filmmaking, collaboration can bring great results.

Armando Bo is a powerful and well-known commercial director who I’ve known for many years. Giacobone is his cousin, a sensitive and talented writer who has written several short stories and is about to publish his first novel. They are both young, talented and Argentine football freaks. They brought to the script a special innocence and freshness. This is their first time doing this but it will definitely not be the last.

Since I first started writing Biutiful, I always thought of Javier Bardem for Uxbal. Nobody else could have brought to the character what he has brought. I could not have made this film without him because for me, he alone was Uxbal. For many years, Javier and I had been trying to work together. I thought, this character will be the bridge that will get us together on set. My style and process of working with actors is not light or easy. I give of myself fully on each project and I demand the same from the actors. I am obsessed with perfection, or what I consider perfection.

Physically and emotionally it is a tough ride. Well, bringing Javier into the equation, it was as if the Hungry and the Starving got together… and we were both yearning to be satisfied. Javier is not just an outstanding actor; he is one of a kind. Everybody knows that. He prepares exhaustively and writes extensive notes about his character. He is committed, intense and obsessed with excellence as well. But what Javier has that makes him so special and unique is a weight, a gravity, an ominous presence on the screen that is based on his deep, strong reflectiveness and his profound interior life. That’s something that can’t be learned. It’s something (angel or devil) that you either have or you don’t.

Unlike my other films where I shot different stories with different actors over several weeks, this one was a looong and intense shoot with Javier in almost every scene, always carrying the film, literally, on his back. The precision and emotional intensity required in every scene was not easy to sustain, especially while trying to balance this act with non-actors and kids. During the Autumn and Winter of 2008/09,

Javier Bardem, the man I knew, just disappeared in order to give life to Uxbal. We knew it would be like climbing Mt. Everest, every day tougher than the one before. We planned and discussed the route. I designed the visual grammatical language and every single aspect of the film — the chronological shooting order, wardrobe, production design, camera movements and even the use of different formats in different phases of the film – in order to help him navigate and arrive where we both wanted to go: from a tough, tight, controlling guy to a man who is liberated, who understands surrender and has gained the wisdom to see and feel the light through his pain. We both gave a lot of ourselves and the story demanded of us to go into dangerous territory from which it is sometimes hard to come back. A film like this drains you, but that extraordinary effort and sacrifice was proportionate to the immense artistic satisfaction that we both shared.

One of the most difficult roles to write and to cast was that of Marambra. Bipolarity, a complex emotional disorder sometimes called manic depression, can be too easily caricatured. I was looking for a very specific vibe and spirit. I held casting sessions all around Spain, and though I saw a lot of very talented actresses there, I couldn’t find what I was looking for. Three weeks before principal photography began, I still hadn’t found her and was close to postponing the shoot. I did an open casting session in Argentina, where we saw Maricel Alvarez.

Even in a video test, I knew it was her. Maricel flew to Spain and after 24 hours without sleeping and a text she had just received 24 hours prior to that, she did the most extraordinary rehearsal test I have seen. I did a camera test with her, too, before she returned to Argentina 12 hours after she had arrived in Spain. I put her in front of a film camera for the first time in her life and I asked her, without doing anything, to imagine certain images or circumstances I was suggesting to her. All the set and crew was quiet. One minute later I had goose bumps on my skin and my eyes were watering. It was just pure alchemy and magic. Maricel brought the danger and the tenderness Marambra needed. She has been an extraordinary theater actress for years with a range and craftsmanship very hard to find on this planet.

For the role of Igé, we looked at more than 1200 women in Spain and Mexico. Diaryatou Daff was found in a downtown Barcelona salon where she worked cutting hair. She is Senegalese and, like hundreds of thousands of other African women, she risked her life and left her country to look for a job to help maintain her family members. Her life hasn’t been easy. She was married when she was 15 to a 50 year-old man, according to a Senegalese tradition where a maternal uncle can choose who a girl will marry. She escaped from this violent man and later married a nice young man and had a child with him. Living in a small town in a desperate economic situation, she decided to look for a job in Spain, and when I cast her, she hadn’t seen her son for more than 3 years. Working day and night, she supports not only her husband and child but 30 other people who depend on the little money she is able to send back to Senegal. Diaryatou was always afraid she might lose her job in the hair salon.

While we were rehearsing I could sense the clear understanding she had for the character I wanted her to play. She did it with such honesty and profundity — just carrying a pillow as if it were her child, I would hear her voice breaking up. The story of Igé was her story. I have never experienced a person in a film whose life was this close to her character. Reality was dancing with fiction in front of my eyes.

She struggled while making the film but her commitment to speaking in the name of millions of women like her was bigger. I always liked the idea that Igé starts out looking like a secondary role, but without seeing her coming, she ends up a cornerstone of the story. She is Mama Africa — a rational, intelligent, loving mother. That it is Diaryatou in real life. Subtle, talented, sensitive, beautiful and more than anything, real.

Kids are always difficult to find. The scenes with the kids were very challenging due to the subject matter of the events and, in this case, the physical characteristics of Bardem and Maricel didn’t make it easier. We found Guillermo to play Mateo early in the process but trying to find Uxbal’s daughter put all of us on edge. It was only 2 weeks before the start of production, when we had resigned ourselves to continue without her, hoping we would find her, that I was doing a technical scout in a local school where we would be shooting. Suddenly, Ana, who happens to study in that school, tapped my back and ask me what I was doing. I turned and saw her. I said, “I am making a movie.” And she said, “I would love to be in it.” And that was that. She was an angel knocking on the door of a desperate man looking all over Spain without knowing that the answer was at the end of his nose.

I could spend hours telling you about Eduard Fernández, Ruben Ochandiano, Cheng Tai Shen, Luo Jin, Martina Garcia and all the great cast of actors who were with us, but I prefer you see their work, which will be better than anything I can say about it.

As always, I had the privilege of working on this film with my old-time partners in crime, the same rock ‘n roll band whose bass-line, drums and instruments make the music richer and more joyful, as we moved away from the cold and technical paper score which every film must depart from to the land of memories, desires, logic, dreams, suggestion and subjective reality of light and images.

As always, I dedicated this film to a family member — not because they are part of my family but because they are the reason, the source, or who I want to speak to directly through the film. This one is for my Father, and he knows well why.

Biutiful (2010)

Directed by: Alejandro González Iñárritu

Starring: Javier Bardem, Maricel Álvarez, Hanaa Bouchaib, Eduard Fernández, Guillermo Estrella, Lang Sofia Lin, Xiaoyan Zhang, Hanaa Bouchaib, Diaryatou Daff, George Chibuikwem Chukwuma

Screenplay by: Alejandro González Iñárritu

Production Design by: Brigitte Broch

Cinematography by: Rodrigo Prieto

Film Editing by: Stephen Mirrione

Costume Design by: Bina Daigeler, Paco Delgado

Set Decoration by: Lluïsa Ferré, Laura Musso, Joan Sabaté

Art Direction by: Marina Pozanco: Sylvia Steinbrecht

Music by: Gustavo Santaolalla

MPAA Rating: R for disturbing images, language, some sexual content, nudity and drug use.

Studio: Roadside Attractions

Release Date: December 29, 2010