Designing and Lensing the Film

“Something coppery red is moving. It looks like flames—waving, disappearing, waving again at the whim of the wind.” —Wes Craven

My Soul to Take gave director Craven the opportunity to work with a new crew for the first time in two decades. “It’s the first movie I have made in 20 years that is totally separate from the group of people that I have mostly made movies with,” he offers. “Since my regular crew was not available, we decided to put ourselves out into the film world and work with all new people.”

During his search for a cinematographer, a friend of Craven’s recommended Petra Korner, who had recently shot The Informers for director Gregor Jordan. Craven had heard only positive feedback about her work on that film, as well as her efforts on The Wackness, which debuted at the Sundance Film Festival. Recalling their initial meeting, Craven says: “Into the room came this young, vital woman who bounced in with solid ideas and confidence. We thought, ‘Why not?’ We decided to go with somebody new, and we’re so pleased we did.”

Adam Stockhausen, who had previously worked as an art director on The Darjeeling Limited, served as a first-time production designer on My Soul to Take. He was one of many new crewmembers who took this opportunity to impress with his skills. “There are a number of people in this film who went up a level and have had the opportunity to stretch their wings,” says Craven. “We were working with Anthony Katagas, a producer who has made five films in Connecticut, so I knew we would be on solid ground. Within a week, we were all great.”

The team decided to film in Connecticut, where Craven’s original version of the film The Last House on the Left was made years earlier. They shot in the state for 47 days—beginning in April 2008 and wrapping in June. But it was Monterey, California, not the Northeast, that served as the inspiration for one of the film’s most unique design elements: the California condor.

Labunka, who refers to the massive bird “as another character in the film,” explains: “Bug and Alex make a giant, terrifying mechanical condor with which they terrorize their class. The idea grew from Wes’ originally setting the story in Monterey, where there is a condor rescue mission. When we took the film to Connecticut, we decided to keep the condor in the script…as we were very invested in this part of the story.”

Once they had scouted the locations, Craven discovered that “Connecticut as a setting had a lot that was similar to Northern California, particularly the forests and streams everywhere.” He admits he “always wanted the film and setting to be very primal with earth, wind, fire and water. As it turned out, Connecticut was the place to do it.”

In the Northeast, the team took advantage of the natural surroundings, weaving in story ideas through different elements. In particular, the spectacular waterfalls around Kent, where most of the ritual sequences were shot, proved breathtaking inspiration to Craven and DP Korner.

The filmmakers were particularly fortunate to find the bridge location where they filmed one of the victim’s bodies as he fell. Offers producer Labunka: “We found this abandoned bridge that had been built in the early 1900s by German iron workers. We had just one night to shoot the scene, and as we arrived in the valley, the fog rolled in. It was just beautiful. Usually fog lifts within an hour, but it settled until we had finished the entire sequence; it sat at a perfect level for Wes.”

The most demanding aspect of the production for the cast and crew was the five weeks of night shoots, all located deep in the woods. “We worked with the crew to slog through ice and choked rivers,” recalls Craven, “not to mention the fact that we were stung by bees and bitten by ticks.”

Ever the optimist, Raúl Esparza describes the experience as “a hell of a lot of fun.” He laughs, “There’s nothing like wielding a knife while you’re covered in blood, screaming at people at four or five in the morning. It was total mayhem, but a great time.” Working on stunts and with a special effects crew was a new experience for the Broadway actor. “I picked up on the stunts and the fight choreography pretty quickly…except for the big stuff like when people start flying out of windows.”

During the ambulance scene in which the killer attacks EMT Jeanne-Baptiste, Esparza managed to remain lighthearted. “They were shaking the ambulance, and I was covered in so much blood that it had coagulated over the course of the day. I became a human Post-it. Everything that moved stuck to me— blankets, people, knives—so I got the worst case of the giggles. Wes assured me it was fine; there was so much howling and screaming going on, you couldn’t tell it was laughter.”

The ambulance stunt turned out to be one of the most spectacular moments in the film, and Craven has nothing but praise for stunt coordinator MANNY SIVERIO. “Every time he would give us a stunt, it made us gasp,” the director recalls. At first, Craven had planned for the ambulance to go up a ramp and roll over a few times, but very quickly the team realized that the square emergency vehicle wouldn’t roll. “In the end, Manny devised a ramp jump that put the thing 24 feet in the air, like a phenomenal football. WES CRAVEN prepares for a scene.

The crash just took our breath away. We certainly got a lot of bang for our buck.” In order to bring Craven’s vision to the screen, he hired Silent Hill’s AARON WEINTRAUB as the VFX supervisor. For Weintraub, it was the opportunity to work with a director “who has informed a whole generation of mimickers.” Still, he says, “It’s great to work with the master of them all. It’s not just about the blood or about seeing the visceral, gory things. It’s a lot more psychological. With Wes, there’s more to the mood and lighting and the way shadows play. This gives an overall psychological creepiness that informs the visuals and works on a higher level.”

The bulk of the VFX team’s work was to create the town across from the river, since nothing like that existed at the location chosen in Connecticut. “Most of the effects revolve around the Ripper ritual sequence on the riverbank in the middle of the night,” says Weintraub. “The idea is that the town is across the river, and there weren’t any towns opposite a river in any of our practical locations. Through matte painting and digital projections onto 3-D geometry, we created this world of the town. It wasn’t practical to shoot everything with a blue screen, which meant a lot of rotoscoping and painstaking compositing with details such as little branches and twigs put in later.”

In the film, the river symbolically represents the divide between the two worlds of the town and the woods, and the filmmakers wanted to keep it as realistic as possible. “There are great natural details in the water where the light picks up off the ripples. As much as possible, we maintained the real life that Wes had created and added to it where we needed to,” says Weintraub.

For the SFX team, there was a healthy amount of gore and blood enhancement involved in creating the film. “That’s all the fun stuff we like to do,” says Weintraub. During filming, they endeavored to practically craft as much of it as they could, to avoid unnecessary CGI in postproduction. Notes Weintraub: “We added extra blade tips to knives and other implements that people were stabbed with.”

At the end of a tough and demanding shoot, Craven shares: “I can honestly tell you that this is a movie where I feel like I’m really on my game. I think it has a lot to do with working with a great crew. Everyone put their heart and souls into it. It’s come to life in a way that I’m very excited about.”

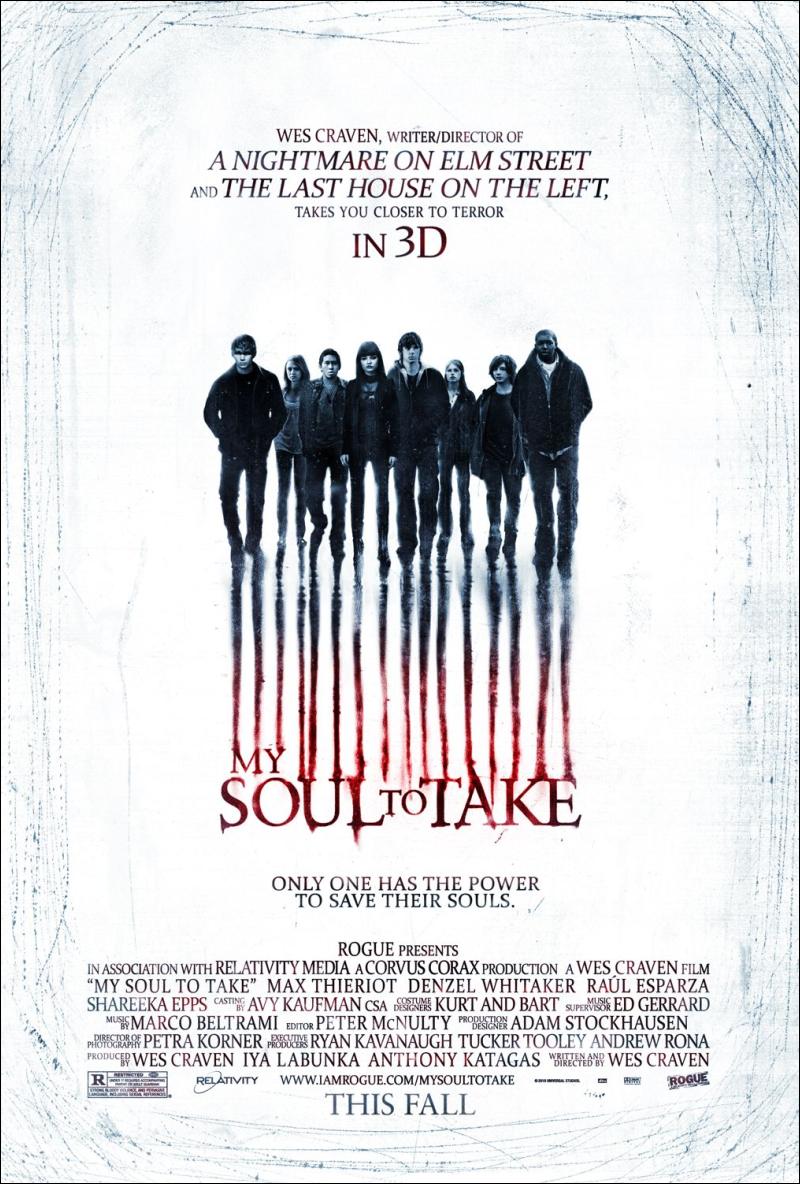

My Soul to Take 3D (2010)

Directed by: Wes Craven

Starring: Nick Lashaway, Zena Grey, Max Thieriot, Denzel Whitaker, Dennis Boutsikaris, Emily Meade, Jessica Hecht, Paulina Olszynski, Frank Grillo, Elena Hurst, Shareeka Epps, Harris Yulin

Screenplay by: Wes Craven

Production Design by: Adam Stockhausen

Cinematography by: Petra Korner

Film Editing by: Peter McNulty

Costume Design by: Kurt and Bart

Set Decoration byB Carol Silverman

Art Direction by: Jack Ballance, Brianne Zulauf

Music by: Marco Beltrami

MPAA Rating: R for strong bloody violence, and pervasive language including sexual references.

Distributed by: Rogue Pictures

Release Date: October 29, 2010