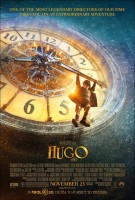

Taglines: Unlock the secret.

Set in 1930s Paris, an orphan who lives in the walls of a train station is wrapped up in a mystery involving his late father and a robot. Hugo Cabret is an orphan boy living a secret life in the walls of a Paris train station. When Hugo encounters a broken automaton, an eccentric girl, and the cold, reserved man who runs the toy shop, he is caught up in a magical, mysterious adventure that could put all of his secrets in jeopardy.

Although the film is based on a children’s book and features pre- teen lead characters, this over two-hour period film will probably have most of its appeal to older adults, especially film history fans. The adult stars such as Ben Kingsley and Sacha Baron Cohen have smaller supporting roles to the young leads. There is no objectionable content except for a couple of action sequences that may be intense for very young kids.

Film Inspires Author, Book Inspires Filmmaker

Growing up in a section of New York City known as ‘Little Italy’ in the 1940s and ‘50s, a young Martin Scorsese found a deep connection inside the movie houses of the time—not just to the experience of viewing motion pictures, but also a closeness to his father, who sat with him in the darkened auditorium, fostering the future filmmaker’s nascent love of the art form. So when Brian Selznick’s award-winning novel The Invention of Hugo Cabret landed on his desk via prolific producer Graham King (who had previously collaborated with Scorsese on three films), the Oscar®-winning filmmaker found the tale profoundly resonant. For Scorsese, “It was particularly the vulnerability of a child alone that was striking. Hugo’s living in the walls of this giant engine of a sort—the train station—on his own, and he’s trying to make that connection with his father, whom he has lost.”

Scorsese remembers, “I was given the book about four years ago, and it was one of those experiences…I sat down and read it completely, straight through. There was an immediate connection to the story of the boy, his loneliness, his association with the cinema, with the machinery of creativity. The mechanical objects in the film, including cameras, projectors, and automatons, make it possible for Hugo to reconnect with his father. And mechanical objects make it possible for the filmmaker Georges Méliès to reconnect with his past, and with himself.”

Scorsese, in turn, shared the book with his youngest daughter, which only confirmed his belief that the story held a magical quality: “In reading books to my daughter, we re-experience the work. So it’s like rediscovering the work of art again, but through the eyes of a child.”

Author Brian Selznick recalls the genesis of his book: “At some point I remember seeing ‘A Trip to the Moon,’ the mesmerizing 1902 film by Georges Méliès, and the rocket that flew into the eye of the man in the moon lodged itself firmly in my imagination. I wanted to write a story about a kid who meets Méliès, but I didn’t know what the plot would be. The years passed. I wrote and illustrated over 20 other books. Then, sometime in 2003, I happened to pick up a book called Edison’s Eve by Gaby Wood. It’s a history of automatons, and to my surprise, one chapter was about Méliès.”

It seems that Méliès’ automatons (mechanical figures, powered by inner clockwork, which appear to perform functions on their own) were donated to a museum once the filmmaker passed—they were stored in the attic, where they ended up largely forgotten, ruined by the rain and eventually, thrown away.

Selznick continues, “I instantly imagined a boy climbing through the garbage and finding one of those broken machines. I didn’t know who the boy was at first, and I didn’t even know his name… I thought the name Hugo sounded kind of French. The only other French word I could think of was cabaret, and I thought that Cabret might sound like a real French name. VoilaÌ…Hugo Cabret was born.”

Research into automatons and clocks, the life of Méliès and the City of Lights in the 1920s and ‘30s fueled the author’s imagination, and the tale of an adventurous boy who lives within the walls of a train station in Paris took life, interwoven with the stories of the colorful characters that surround him. Add in the threads of the discovery of both an abandoned automaton and a largely forgotten filmmaker, and you have Selznick’s beautifully illustrated The Invention of Hugo Cabret (A Novel in Words and Pictures. Published in 2007, The Invention of Hugo Cabret (A Novel in Words and Pictures) won the 2008 Caldecott Medal (awarded by the Association of Library Service to Children to the artist of “the most distinguished American picture book for children”) and The New York Times’ Best Illustrated Book of 2007. It was a number one New York Times Bestseller, and a Finalist for the National Book Award.

Producer Graham King: “My producing partner Tim Headington and I were enchanted by Brian Selznick’s book. Immediately we thought it would be a beautiful story for Martin Scorsese to create into a piece of cinema.”

The team turned to John Logan—their writer on “The Aviator”—to take Selznick’s words and illustrations and transform them into a screenplay. As with most book-to-movie conversions, some things had to change. Logan comments, “I had to cut and change some elements of Brian’s book to make a more streamlined, shorter movie. The drawings were extremely helpful, because they reminded me of movie storyboards. In effect, they presented a road map for me to follow. In fact, the screenplay opens with a description very similar to Brian’s first drawings in the book.”

Producer King addresses the perhaps unexpected pairing of Scorsese and the story of Hugo: “All of Scorsese’s films have a specific sensibility to them, and ‘Hugo’ is no different. The beautiful imagery and fantastic performances are all there. The main difference is that this film is not made solely for an adult audience—it is for everyone.”

To try and replicate the experience of moving through Selznick’s work, Scorsese also turned to a different film format. He says, “As moviegoers, we don’t have the advantage of the literature, in which you can become aware of Hugo’s inner thoughts and feelings. But here, we have his extraordinary face and his actions, and we have 3D. The story needed to be changed to a certain extent, so some elements were dropped from the book. But I think that certain images—particularly in 3D—cover so much territory that the book resonates in them.”

Scorsese strove to honor the author’s work with every decision, and comments, “Brian Selznick and his book were always an inspiration. We had copies with us all the time. The book has such a distinctive look, whereas our film has its own look and feel, very different from the book, which is in black and white, for one thing. We really went for a blend of realism and a heightened, imagined world.”

Balancing Realism and Myth

To re-create the world of Paris in the early ‘30s, as filtered through Hugo Cabret, a fictional character, Scorsese aimed to create, as he put it, “a balance of realism and myth.” He brought researcher Marianne Bower onboard, who looked to lend authenticity, supported by historical photographs, documents and films of the period. She narrowed her search to isolate the time period of 1925 to 1931.

As a course of study for the creative departments, members of Team Hugo watched about 180 of Méliès’ films, about 13 hours’-worth, along with films of René Clair and Carol Reed, avant-garde cinema from the 1920s and ‘30s. They watched films of the Lumière brothers, and silent films from the ‘20s to study period tinting and toning. Reference was not limited to ‘moving pictures,’ as they also studied still photography of Brassaï (Hungarian photographer Gyula K. Halász, who memorialized Paris between the Wars) for the period look of the Parisian streets and the appearance and behavior of the background actors.

While some location filming would take place, the majority of filming was to be done at England’s Shepperton Studios, where the production designer Dante Ferretti would supervise the construction of Hugo’s world, which included a life-size train station with all of its shops, Méliès’ entire apartment building, his glass studio building, a bombed-out structure next door, a fully stocked corner wine shop and an enormous graveyard marked by huge monuments and stone crypts, among others.

The centerpiece of the tale, the station, was an amalgamation of design elements and structures lifted from multiple train stations of the period—some still in existence, which proved helpful to many of the artists; sadly, Gare Montparnasse was destroyed and rebuilt anew in 1969. Per Scorsese, “Our station is a combination of several different train stations in Paris at that time. Also, our Paris is really a heightened Paris…our impression of Paris at the time.”

Ferretti’s impressive sets were brought even more into the period with the help of set decorator Francesca Lo Schiavo, who joyfully admits that she had the pitiable task of repeated shopping trips to flea markets in and around Paris. She also supervised the reproduction of posters from 1930-31 for use in the station and on some building exteriors. Some design elements were also inspired references to some of the best of French cinema.

An experience from Ferretti’s youth also proved quite useful to the designer—at age eight, the father of his best friend worked with clocks, and once he began to incorporate them into his designs, “all my memory about this came back…I had forgotten everything.” (The actual construction of the clocks themselves was done by Joss Williams of special effects.)

When finished, the main hall of the train station filled a soundstage, running 150 feet in length, 120 in width and 41 in height. The overwhelmingly immersive environment allowed Scorsese and director of photography Robert Richardson to film all the movement, bustle and collision of the multiple stories dictated in Logan’s screenplay, including a rather breathless chase between the Station Inspector and Hugo.

Costume designer Sandy Powell also looked to the past for information and inspiration, but also, played fully with the idea of Scorsese’s ‘impression of Paris’ agenda. Vintage clothing figured heavily—for reference and for actual use—but for those actually worn by an actor, they had to be subjected to strengthening (at the very least) or even re-made.

Powell found Hugo’s signature striped sweater, then had copies made (several sets of identical costumes were necessary for characters who appear in largely unchanged outfits throughout the film). When Helen McCrory appears as a constellation in one of Méliès’ films, she was outfitted in a found skirt (from an old costume or ball gown from the ‘40s or ‘50s, Powell surmises), which, with added bodice, was refashioned into the airy costume befitting a ‘star.’ Kingsley’s costumes as Méliès were taken directly from photographs, then padded, to not only give the actor a more slumped silhouette, but also to remind him not to stand up straight.

Hugo

Directed by: Martin Scorsese

Starring: Chloë Grace Moretz, Asa Butterfield, Helen McCrory, Christopher Lee, Emily Mortimer, Jude Law, Frances de la Tour, Gulliver McGrath, Sacha Baron Cohen

Screenplay by: John Logan, Brian Selznick

Production Design by: Dante Ferretti

Cinematography by: Robert Richardson

Film Editing by: Thelma Schoonmaker

Costume Design by: Sandy Powell

Set Decoration by: Francesca Lo Schiavo

Music by: Howard Shore

MPAA Rating: PG for mild thematic material, some action / peril and smoking.

Studio: Warner Bros. Pictures

Release Date: November 23, 2011

Hits: 121