Taglines: What are you really worth?

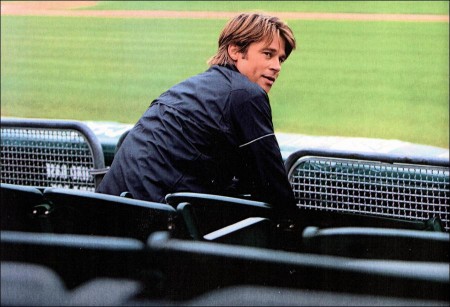

Based on a true story, Moneyball is a movie for anybody who has ever dreamed of taking on the system. Brad Pitt stars as Billy Beane, the general manager of the Oakland A’s and the guy who assembles the team, who has an epiphany: all of baseball’s conventional wisdom is wrong. Forced to reinvent his team on a tight budget, Beane will have to outsmart the richer clubs.

The onetime jock teams with Ivy League grad Peter Brand (Jonah Hill) in an unlikely partnership, recruiting bargain players that the scouts call flawed, but all of whom have an ability to get on base, score runs, and win games. It’s more than baseball, it’s a revolution – one that challenges old school traditions and puts Beane in the crosshairs of those who say he’s tearing out the heart and soul of the game.

Production Information

In 2003, former Salomon Brothers bond trader turned author Michael Lewis, at the time best known for such business and politics bestsellers as Liar’s Poker and The New New Thing, published a book about baseball. Only it wasn’t just about baseball. On the surface, it was about how the under-funded, underrated Oakland A’s took on an unfair system of big-money and powerhouse teams. But it was really about the fascinating mix of men behind a major cultural shift and how a risky vision, born from necessity, becomes reality, when a ragtag team of cast-offs rejected due to unfounded biases, get the chance to finally prove their potential.

Now, Lewis’s book has been adapted into a feature film, Moneyball, starring Brad Pitt as Billy Beane, the A’s General Manager – the man who would have to think differently and reinvent the rules if his team was going to compete. “Moneyball is a classic underdog story,” says Pitt, who also serves as a producer of the project. “They go up against the system. How are they going to survive, how are they going to compete? Even if they do groom good talent, that talent gets poached by the big-market, big-money teams. And what these guys decided was, they couldn’t fight the other guy’s fight, or they were going to lose. They had to re-examine everything, to look for new knowledge, to find some kind of justice.”

At first glimpse, Lewis’ best-selling and groundbreaking book does not lend itself to a film adaptation. The book is a study of inefficiencies and oversights within the markets of the game of baseball and features case studies of undervalued items, (players, strategies, tactics), using analyses of statistics and theories. But at the center of it all is Billy Beane on a quixotic quest and as his story unfolds, something unexpected happens. His pursuit of a championship leads to something larger and more meaningful. The hallways and front offices of the Oakland Coliseum become an unlikely setting for inspiration and redemption.

Lewis’ book shed light on the hindrances of groupthink and how irrational intuition and conventional ‘wisdom’ have dominated institutions throughout history. Challenging a system invariably provokes a fight. The film Moneyball builds its foundation from the experience of one man who chooses to take on that fight. Piercing through the layers of statistics, the film finds the quieter, deeper, and more personal story of Billy Beane, which bristles with moments of self-doubt and real life courage.

“Whenever a book is adapted into a movie, there are two possibilities: either the filmmakers stick to the book, or they make up their own story,” says Michael Lewis. “With Moneyball, frankly, I wondered how they were going to do it, because the book doesn’t necessarily have a single narrative or the kind of dramatic arc you usually see in a movie. So it was truly tough to crack the code and get it right and it was an extremely pleasant surprise to see that Bennett and the screenwriters did the impossible – not only did I love the movie, but I was stunned by how well it represents my book. It is honest and true to what happened with Billy and the A’s and what they achieved.”

That story is very close to Pitt and one that he was uniquely suited and positioned to see through, as both an actor and a producer. He has played a variety of roles and characters and often makes surprising choices – yet has never played an iconoclast like Billy Beane, a fiercely competitive middle-aged family man, driven by a desire to win – and perhaps, even more importantly, reinvent himself. Pitt’s determination to play this part on the screen resulted in a dogged support from the actor/producer, one he saw through a long development process in the effort to get it right. Moneyball found a match with director Bennett Miller. Miller had a garnered a rare first-timer’s Oscar® nomination for Best Director with his debut film, the acclaimed Capote.

“It was Bennett who cracked it,” says Pitt. “The book really isn’t a conventional story, and because of that – to do it justice – Bennett did not want to make a conventional movie. We were all very passionate about the project, but it is Bennett’s desire to make a certain kind of movie that ultimately formed the movie that is on the screen.”

“Brad had personal reasons for wanting to make this story,” says director Bennett Miller. “Over the course of making the film, Brad revealed himself to be more than just a great actor— he is a great collaborator and producer. We saw the movie as a classic search-for-wisdom story – I think there’s something thrilling about people relinquishing long-held, conventional, conformist, universal beliefs. It gets really exciting when there are personal consequences to it. On the surface, he’s trying to win baseball games, but beneath it all, there’s something he’s trying to work out. That is a timeless story.”

“In many ways, Billy’s going up against an institution – one that many smart individuals have dedicated their lives to,” says Pitt. “The minute you start questioning any of those norms, you can be labeled a heretic or dismissed as foolish. These guys had to step back and ask, ‘If we were going to start this game today, is this how we’d do it?’ A system that has worked for 150 years doesn’t work for us – I think that’s applicable to the moments of flux we’re experiencing today.”

“The film is about how we value things,” Pitt continues. “How we value each other; how we value ourselves; and how we decide who’s a winner based on those values. The film questions the very idea of how to define success. It places great value on this quiet, personal victory, the victory that’s not splashed across the headlines or necessarily results in trophies, but that, for Beane, became a kind of personal Everest. At the end of the day, we all hope that what we’re doing will be of some value, that it will mean something and I think that is this character’s quest.”

Miller adds, “I wasn’t interested in the tropes of sports movies. I’d rather not end a film with a hero carried off on the shoulders of teammates in a stadium where fans are screaming their heads off, champagne corks flying, trophies, fireworks, and all of that. I prefer the quiet triumphs, that might not burn as bright but deeper and more lasting, where you see someone struggle internally and then come out the other side to realize something has changed within them.”

“Bennett has the gravitas and the command as a filmmaker to get to the richer themes and more profound aspects of this story,” says producer Michael De Luca. “Sports movies can be great metaphors for life, and Bennett brings a strong view of contemporary life to the process.”

Though he is a baseball fan, and sparked to the idea of a different cinematic take on the sports world, Miller was also drawn to the deeper fabric of Billy Beane’s story. “I like that you have a character who takes a risk not just to make something of himself, but more so to understand something about himself,” Miller explains. “On the one hand this is a true sports drama, but Billy is trying to do something more meaningful than simply win baseball games – whether he understands that or not.”

Miller says those consequences come up in the questions Beane faces – which, ultimately, are questions we all must face: “How do you compare the value of one thing to another, of one person against another, of the choices in your life?”

One early reader of Lewis’s book was New York-based producer Rachael Horovitz, who connected with the universal appeal of Billy Beane’s trajectory and saw the bones of a great movie. “He is a great character, a complex outsider, flailing on the inside, yet aching to remake the system,” Horovitz says. “He picked himself up and had the courage to start again.”

Horovitz would team with Michael DeLuca and Brad Pitt to complete the production team. Says De Luca: “What got me about the story is how courageous it is to be that lone, original voice at the right time and right place to turn the ship of conventional thinking around.”

After writer Stan Chervin found the essence of the story – focusing on Billy’s relationship with his daughter, Peter Brand, and the team, with all three threads coming to a climax in the A’s 20th consecutive win – screenwriters Steven Zaillian and Aaron Sorkin would face a compelling challenge. Though the film joins a storied cinematic genre, it defies the structure of the typical baseball movie that tilts towards that big championship moment. On the contrary, the film is about redefining the very picture of success. Zaillian and Sorkin would hone in on Beane’s inner drive to succeed – not just for himself but for all the guys who had wound up on the margins of baseball.

Says Zaillian: “Trying to change any venerable institution always leads to the same things: suspicion, fear, contempt and condemnation. This, along with the collision that results, is the central theme in Moneyball. It’s the central theme any time, in any field – art, science, industry, politics, sports – when someone has, and acts on, a new idea.”

Adds Sorkin: “I don’t think Moneyball is anymore about Sabermetrics than The Social Network is about coding. Tired of losing and not having the resources to win conventionally, he takes a chance on a very unconventional strategy.”

Sorkin continues: “Necessity is a great motivator. Billy knew that if he played the game the same way as the Yankees he’d lose. He had to change the game. The first guy through a wall always gets bloodied and Billy takes his share of hits – from the fans, from sports writers and baseball experts, from his manager, scouts and even from history. A lot of what the story is about is finding worth in uncommon places.”

“Of course one looks at a person’s background when trying to find keys to their character, and Billy’s, like any player’s, was well documented, his successes and failures on the field. But you have to be careful not to rely too heavily on that,” says Zaillian. “A person’s character often has little to do with their past, so you also have to look at their present, who they are, how they behave, what they think now . . . One of the great things about baseball is its offer – on a day-by-day basis – of redemption. The concept of a ‘slump’ assumes you’ll get out of it. You’ll hit better tomorrow. For the rest of us this promise of opportunity is vague at best. For players it’s clear, tangible, measurable, possible every day.”

Penetrating the verbiage of that process started with research. “Naturally, I went up to Oakland to get a feel for Billy and the Coliseum,” recalls Zaillian, “and also met with a roomful of scouts – three generations of them – to get a sense not only of their vernacular, but what they think about their job, baseball in general, and how they evaluate young players, both the traditional way – with their eyes, knowledge and gut – and the more statistical ‘moneyball’ way.”

What Billy Beane and his partners in analysis put into practice was not entirely new. Fans, stats junkies and math whizzes had been trying to bring empirical evidence to the sport for years. The concept goes back to baseball historian Bill James, who coined the term “Sabermetrics” to describe a new objective science of using stats analysis to predict the future value of a baseball player. James wrote that the subject of baseball should be approached “with the same intellectual rigor and discipline that is routinely applied, by scientists… to unravel the mysteries of the universe.”

With his insider’s position but his rebel’s demeanor and his own personal mission at stake, Beane was able to cross the gap, bringing the information society to baseball’s halls of power for good.

“I think there was a gotcha moment with Bill James and some other consultants we worked with at that time,” Beane comments. “It was a like solving a mathematical problem. You suddenly understood how to get four from two plus two – you understood that there was a rational way of determining why players and why teams had success. Remember, baseball was still very much driven by potential as opposed to what someone had actually done on the field. It was viewed as an athletic sport and Bill James said it’s the results that matter, not how you get there, and not how the players look doing it.”

Says Lewis: “The ideas weren’t radical – they had existed for two decades. But what was radical was how Billy applied the knowledge, imposing these ideas that had existed outside the game onto the game. He broke down the walls between the outsiders and the insiders who had the power. And today’s world reflects the damage he did to those walls. It had a profound effect not only on baseball but on all of sports management.”

“Michael Lewis likes stories about unconventional thinkers,” says Miller. “That’s what Moneyball is – a story about a character whose past and whose circumstances lead him to and require him to think differently. I like that you have a character who takes a risk not just to make something of himself, but more so to understand something about himself. On the one hand this is a true sports drama, but Billy is trying to do something more meaningful than simply win baseball games – only even he doesn’t really understand that until he starts to turn things around. All of a sudden this baseball season, which is a David versus Goliath story, becomes not just one competitive man’s desperate attempt to win games. It’s really a trial, an attempt to prove something that would, if proven true, explain in part why his life turned out the way it did, which is a thrilling idea.”

Moneyball

Directed by: Bennett Miller

Starring: Brad Pitt, Jonah Hill, Robin Wright, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Kathryn Morris, Tammy Blanchard, Vyto Ruginis

Screenplay by: Michael Lewis, Stan Chervin, Stephen J. Rivele, Aaron Sorkin

Production Design by: Jess Gonchor

Cinematography by: Wally Pfister

Film Editing by: Christopher Tellefsen

Costume Design by: Kasia Walicka-Maimone

Set Decoration by: Nancy Haigh

Art Direction by: Brad Ricker, David Scott

Music by: Mychael Danna

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for some strong language.

Studio: Columbia Pictures

Release Date: September 23, 2011

Hits: 120