Taglines: You only live once. How many chances do you get?

Screenwriter Peter Morgan and director Fernando Meirelles’ 360 combines a modern and dynamic roundelay of stories into one, linking characters from different cities and countries in a vivid, suspenseful and deeply moving tale of love in the 21st century. Starting in Vienna, the film beautifully weaves through Paris, London, Bratislava, Rio, Denver and Phoenix into a single, mesmerizing narrative.

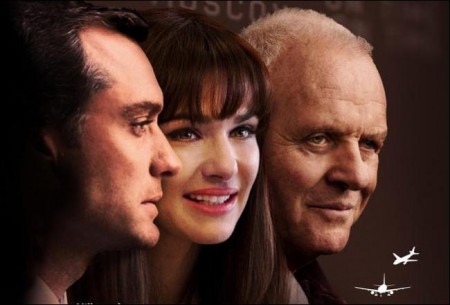

360 is a 2011 ensemble drama film starring Anthony Hopkins, Ben Foster, Rachel Weisz, Jude Law and other international actors. The film, directed by Fernando Meirelles, opened the 2011 London Film Festival. Magnolia Pictures released the film on video on demand on 29 June 2012 and was released in United States theaters on 3 August 2012. The film reunited Weisz and director Meirelles, who worked together on The Constant Gardener (2005). The film follows the stories of couples and their sexual encounters, and was written by Frost/Nixon screenwriter Peter Morgan. It is a loose adaptation of La Ronde.

Film Review for 360

Peter Morgan made his reputation with remarkably perceptive screenplays about British people, mostly real-life ones, going through bad patches in their careers at home (The Damned United, The Queen) and abroad (Frost/Nixon, The Last King of Scotland), and encountering some rather odd people. More recently, however, he’s moved on to a larger canvas involving the mystical and metaphysical, and the results have been less satisfactory.

Hereafter, which Steven Spielberg produced and Clint Eastwood directed, began with an astonishing re-creation of the south-east Asian tsunami, then proceeded with flat-footed banality to tell the parallel stories of three people from different countries (a French TV reporter, an American blue-collar worker and a south London schoolboy) mysteriously linked by their near-death experiences.

His new film, 360, directed by Fernando Meirelles, takes him halfway across the world and back, conjoining the lives of people in half-a-dozen cities in ways of which they’re unaware but to which we’re privy in God-like manner. It belongs to that school of portmanteau pictures the French call les films à sketches which tell a variety of stories consecutively or concurrently with a linking theme, author or geographical location.

One thinks of Ealing Studios’ Dead of Night, of the western Winchester 73 and the Franco-Italian The Seven Deadly Sins. They invariably feature a cast of familiar faces, and the practice goes back to the Depression, when MGM’s Grand Hotel and Paramount’s If I Had a Million (both made in 1932) showed how Hollywood studios kept their stars busy by bringing them together in a single picture.

One of the most famous films of this kind is La ronde, the first of the four masterpieces made by Max Ophüls after his return to Europe in 1950. Featuring some of France’s finest actors, it’s a version of Reigen, Arthur Schnitzler’s 1897 play about a transgressive sexual roundelay in fin-de-siècle Vienna involving people of different classes and backgrounds, several of them near-strangers and likely to be transmitting syphilis. Ophüls somewhat prettified the story, perhaps, but Anton Walbrook as the master of ceremonies was an unforgettably witty, suave and cynical man of the world.

Schnitzler’s play and the Ophüls film are the declared inspiration for Morgan’s screenplay: his title derives from the 360 degrees of a circle and begins and ends with a chilling sexual transaction that recreates Schnitzler in the internet culture of present-day Vienna. Another influence, one suspects, might be those Alan Ayckbourn plays where the action can move in different directions according to chance events, such as the flip of a coin (Sisterly Feelings) or a decision whether or not to have a cigarette (Intimate Exchanges, which Alain Resnais adapted as Smoking/No Smoking).

So we have a glossy film about fate and destiny with ludic trimmings, suggesting that all (or at least a large part) of human life is here, performed by an international cast headed by Anthony Hopkins, Rachel Weisz, Ben Foster and Jude Law, and supported by actors who are star names in their own countries. There are business tycoons from Germany and Britain, Austrian pimps, Russian gangsters, a French dentist, an American sex offender on parole, a Brazilian photographer and various wives and partners. They spend a lot of time flying, conducting dodgy business deals, engaging in sex or looking for love, and almost without exception they’re anxious, depressed and (in the case of those with some vestige of conscience) guilt-ridden.

They travel between Vienna, Paris, Berlin, London, Denver and Phoenix, staying at smart, anonymous international hotels of the sort Kenneth Tynan once called the Adolf Hilton, and living in uncluttered glass-and-steel apartments furnished with reams of Eames. The only people who don’t belong to this affluent, privileged lifestyle, nor aspire to it, are the sex offender (Ben Foster) and his sympathetic prison psychologist (Marianne Jean-Baptiste).

Dramatically the action kicks off when the lonely British car executive (Jude Law) decides at the last moment not to use the services of a Slovakian prostitute in Vienna. This has the unexpected consequence of his wife dropping her Brazilian lover and Law himself being blackmailed by a business associate.

The film’s best sustained sequence (and its most dangerous and affecting one) involves a troubled Brazilian girl, the sex offender and a retired middle-aged Englishman (Hopkins) searching for his missing daughter, a quest that leaves all of them stranded together during a snowstorm at Denver airport. (This is certainly better than Anthony Asquith and Terence Rattigan’s 1963 airport movie The VIPs.)

The most exciting sequence is the most commonplace: a couple of gangland killings in a Viennese hotel, which with heavy irony take place while two other characters drive around the city’s famed Ringstrasse. The one really memorable scene occurs in Phoenix, when Hopkins attends an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. His brilliantly delivered speech draws together and gives vitality to the film’s themes, about taking the chances we’re given and playing the hand we’re dealt by life.

360 has a gleaming surface and a knowing air, but essentially it reflects (and this is something hinted at in an accompanying note by Morgan) the lives of people who spend too much time in planes and confuse the ennui induced by jet lag with authentic Weltschmerz. The film’s gifted Brazilian director, Fernando Meirelles, who addressed urgent problems in City of God and The Constant Gardener, was similarly out of touch with the real world in his last film, Blindness, a hollow allegory about an unnamed police state whose citizens suddenly lose their sight. At the end one feels that 360 isn’t concerned with taking decisions or dealing with fate. It’s less about understanding the butterfly effect than observing some urban moths flitting around a guttering candle.

360 (2012)

Directed by: Fernando Meirelles

Starring: Lucia Siposová, Gabriela Marcinkova, Jude Law, Dinara Drukarova, Rachel Weisz, Juliano Cazarré, Ben Foster, Anthony Hopkins, Mark Ivanir, Patty Hannock, Jamel Debbouze

Screenplay by: Peter Morgan

Production Design by: John Paul Kelly

Cinematography by: Adriano Goldman

Film Editing by: Daniel Rezende

Costume Design by: Monika Buttinger

Set Decoration by: Anna Lynch-Robinson

MPAA Rating: R for sexuality, nudity and language.

Distributed by: Magnolia Pictures

Release Date: August 3, 2012

Hits: 116