Filmed in the seemingly well-appointed Mineola high school on Long Island (though not identified), Detachment is directed by the British video director who made the not uninteresting American History X. It’s the ultimate sink school picture towards which all movie indictments of public education have been heading since Blackboard Jungle 57 years ago. The principal is about to be dismissed, the pupils are dangerously out of control, the staff at the end of their tether, the parents aggressively uncooperative, the authorities ignorant and insensitive.

Then along comes saintly supply teacher Henry Barthes (Adrien Brody), terminally depressed and seemingly carrying a rain-cloud above his head like a halo. He believes the world is without hope but seeks to convey something about the value of literature. Meanwhile he takes a teenage hooker under his wing, tries to help a suicidal pupil and tells the kids it’s bad to dismember cats. At the end, however, he sees the whole school system disintegrating like Poe’s House of Usher. The acting is excellent but the movie is the sort of thing that gives pessimism a bad name.

Detachment is a 2011 American drama film about the high school education system directed by Tony Kaye, starring Adrien Brody with an ensemble supporting cast including Marcia Gay Harden, Christina Hendricks, William Petersen, Bryan Cranston, Tim Blake Nelson, Betty Kaye, Sami Gayle, Lucy Liu, Blythe Danner and James Caan.

Film Review fon Detachment

I was looking forward to seeing Detachment, the new teacher film starring Adrien Brody and directed by Tony Kaye. With a very strong supporting cast (Marcia Gay Harden, Tim Blake Nelson, Christina Hendricks, Bryan Cranston, James Caan) and a compelling trailer featuring Brody as a tortured soul struggling to connect with his students, the movie seemed right up my alley. As a 31-year-old teacher and movie fanatic, I am Detachment‘s target audience; this should have gone well.

Detachment arrived in theaters on March 16. This movie has all of the trappings of an intelligent indie flick—- stellar cast, relevant social issues, and a notoriously egomaniacal director heralded by some as a genius.

It’s hard to know where to begin to explain what a mess this film is. With its contrived story, one-dimensional characters, and in your face stylized visuals, Detachment takes edu-hand-wringing to new, blood-and-tear-soaked depths.

As a film major at NYU, I watched many crappy student films; in fact I made a few myself. Aside from experimental visuals that don’t pay off, the crappiness was most often epitomized by a lack of authenticity in the script. For example, students made police procedurals without having a clue about detectives’ reality — they took shortcuts by guessing or basing their stories on other inauthentic sources.

The results, intended to play as dramatic, came out flat or even silly. Detachment suffers from the same syndrome; the script feels as if the writer (Carl Lund) dreamed up the worst things that could happen in public schools, put them on steroids, populated the scenes with the miserable characters, then let it run wild. In Detachment, suicides (there are two in the movie) aren’t “shocking”— they are a naked ploy for manufactured emotion.

Kaye leans on his audience’s vague, negative prejudices against the public school system. There’s no solid story here, just a bunch of lost/evil souls and a sense of decay. Many details will ring false to anyone who has spent time in a classroom. On his first day as a sub, Adrien Brody’s character enters his English 11 class to find all of the students quietly sitting at their desks waiting for him. Then, after he makes a brief introductory speech, the kids suddenly morph into profane hooligans. Two curse him out and one assaults him, chucking his briefcase across the room.

The movie avoids the very real issue of de facto racial segregation in urban schools. In Detachment, classes are racially diverse and pretty much everyone acts like a deadbeat. The movie takes the easy way out of facing any root causes of public education’s struggles other than lambasting absentee parents— and in this community all of the parents are either absent or over-the-top abusive.

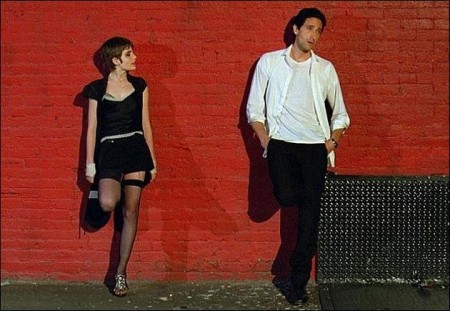

As the film’s centerpiece, Adrien Brody emanates handsome ennui. He plays Henry Barthes, a glazed out guy with no friends and trauma in his past who comes to a nameless urban high school as a recommended substitute teacher. He doesn’t get mad when kids greet him with virulence and he says a few things about how everyone is in pain and that literature is needed to defend and preserve our minds. All of that would be fine — Brody’s charisma manages to blunt some of the dialogue’s preachiness — except most of Detachment‘s 98-minute running time is eaten by a miscellany of misery that ventures freely into exploitation.

In the world of Detachment, students are mean-spirited, profanity-addicted nihilists. (The one nice girl, played by the director’s daughter, publicly commits suicide.) Teachers are sadsacks or menaces: Tim Blake Nelson plays a teacher who can’t get anyone to listen to him at school or at home, so he hangs daily on the schoolyard chain-link fence in the crucifixion pose, wallowing in his invisibility.

As an overwhelmed guidance counselor, Lucy Liu screams at and ejects an obnoxious student from her office— then weeps about it. William Petersen is a scary, borderline nonverbal teacher who in class shows Nazi images and glowers. Marcia Gay Harden, on the verge of losing her job as principal, delivers a public address announcement while curled in the fetal position on the floor of her office.

Outside of school, Barthes engages in various acts of sadness. He cries on a public bus, takes in and rehabilitates a teenage prostitute (a major storyline that reeks of cliches), role-plays with his dementia-addled grandfather, and screams in the face of a night-shift nurse.

The words “in your face” never left my mind during this film. Visually, director Tony Kaye, who regretfully doubles as director of photography, relies enormously on close-ups, often with point-of-view shots awkwardly placing the subject in the center of the frame. The effect is not arresting, but claustrophobic. Mixed in at tense moments are bits of crude chalk-on-blackboard animation that distract from rather than support the narrative.

Worst of all, the film is peppered with cutaways to Adrien Brody in tight close-up, his hair distractingly much longer than in the action of the film, philosophizing vaguely to an unseen interviewer about lack of fulfillment and generational decline. These seemingly improvised clips carry the intellectual weight of a freshman dorm bull session. (“We’re failing… we’re failing.”) It’s never entirely clear whether Brody is in character as Barthes or if he’s just spitballing.

It all ends with Barthes visiting the teenage prostitute Erica at the “Guardian Angels Foster Care Facility,” a verdant resort-like institution where they share a sunny embrace. Then he goes to school and reads an excerpt from Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher to a classroom that literally transforms into a ravaged wasteland.

My fear is that non-educator audiences will be tricked by the gravitas of Brody (“I’m a hollow man. You see me, but I’m not here.”) and the overall grimness of the story into thinking that this is a valuable portrait of American education. Don’t fall for it; this is a meandering mosaic of unfocused bitterness, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.

Detachment (2012)

Directed by: Tony Kaye

Starring: Adrien Brody, Marcia Gay Harden, Christina Hendricks, William Petersen, Bryan Cranston, Tim Blake Nelson, Betty Kaye, Sami Gayle, Lucy Liu, Blythe Danner, James Caan

Screenplay by: Carl Lund

Production Design by: Jade Healy

Cinematography by: Tony Kaye

Film Editing by: Michelle Botticelli, Barry Alexander, Peter Goddard, Geoffrey Richman

Costume Design by: Wendy Schecter

Set Decoration by: Candice Cardasis, Mary Prlain

Music by: The Newton Brothers

Distributed by: Tribeca Film

Release Date: March 23, 2012

Hits: 90