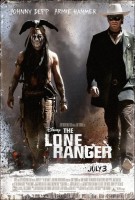

Taglines: Never take dff the mask.

From producer Jerry Bruckheimer and director Gore Verbinski, the filmmaking team behind the blockbuster “Pirates of the Caribbean” franchise, comes Disney / Jerry Bruckheimer Films’ “The Lone Ranger,” a thrilling adventure inf used with action and humor, in which the famed masked hero is brought to life through new eyes. Native American warrior Tonto (Johnny Depp) recounts the untold tales that transformed John Reid (Armie Hammer), a man of the law, into a legend of justice–taking the audience on a runaway train of epic surprises and humorous friction as the two unlikely heroes must learn to work together and fight against greed and corruption.

“The Lone Ranger” also stars Tom Wilkinson, William Fichtner, Barry Pepper, James Badge Dale, Ruth Wilson and Helena Bonham Carter.

The Lone Ranger is an American action western film directed by Gore Verbinski from a screenplay written by Justin Haythe, Ted Elliott, and Terry Rossio. Based on the radio series of the same name, the film stars Johnny Depp as Tonto, the narrator of the events, and Armie Hammer as John Reid (The Lone Ranger).

It relates Tonto’s memories of the duo’s earliest efforts to subdue the immoral actions of the corrupt and bring justice in the American Old West. William Fichtner, Barry Pepper, Ruth Wilson, James Badge Dale, Tom Wilkinson and Helena Bonham Carter also are featured in supporting roles. It is the first theatrical film featuring the Lone Ranger and Tonto characters in more than 32 years.

A Legacy Reborn (2013)

Eighty years after they first rode into the public’s imagination, the classic characters of the Lone Ranger and Tonto remain enduring fixtures of the American cultural landscape. “There’s something about these characters that have appealed to every generation since they were invented,” notes producer Jerry Bruckheimer. “I grew up in Detroit, and ‘The Lone Ranger’ radio and TV shows were part of my youth, and millions of others as well.” On radio, television, theater screens, TV animation, comic strips, books, graphic novels, and video games, the perpetual popularity of these iconic American characters represents a continuum that confirms the continuity of the public’s fascination with them.

The program first made its way onto the airwaves courtesy of WXYZ radio in Detroit, Michigan, on January 30, 1933. The station owner, George W. Trendle, wanted a Western that would appeal to a children’s audience. The character he created was wholesome, honest and an authority figure kids could admire. The concept of the Lone Ranger was thus born and handed off to Fran Striker, a script writer from Buffalo, and the station’s staff director, James Jewell.

Jewell went on to direct “The Lone Ranger” radio series through 1938, by which time it was a national phenomenon. Jewell’s father-in-law owned Kamp Kee-Mo-Sah-Bee in Mullet Lake, Michigan, which became the obvious linguistic inspiration behind Tonto’s name for his friend, the Lone Ranger (Tonto was introduced 11 episodes into the series). It’s believed that the camp was named after an Ojibwe word, “giimoozaabi,” which has been varyingly translated as “trusty scout” or even “someone who does not follow the normal path.” The name Tonto might also derive from another Ojibwe word, “N’da’aanh-too” (pronounced “Nduh-on-toe”) meaning “wild one” or “to change.” Jewell also suggested Gioachino Rossini’s “William Tell Overture” as the program’s theme music.

There were 2,956 radio episodes of “The Lone Ranger” (the last new one was broadcast on September 3, 1954), a 21-year history that actually overlapped the hugely successful television series, starring stalwart Clayton Moore as the titular character and dignified Jay Silverheels as Tonto. This program, which became an international phenomenon, began airing on ABC in 1949 and continued until 1957.

The huge popularity of the show also spun off into two theatrical feature films, “The Lone Ranger” (1956) and “The Lone Ranger and the Lost City of Gold” (1958). But now it’s time for Johnny Depp and Armie Hammer to put their own indelible stamps on Tonto and the Lone Ranger. As they respect some traditions established over the past eight decades, they also fearlessly interpret the characters for an entirely new generation.

Shaping the Story (2013)

As with many ambitious projects, it was a long and winding road that brought the new version of “The Lone Ranger” to fruition. But neither producer Jerry Bruckheimer nor director Gore Verbinski are men to be easily dissuaded once their hearts and minds are focused. “We knew that it was time for ‘The Lone Ranger’ and Westerns to be reborn,” says Bruckheimer, “just as Gore and I knew that it was time for pirate movies to be resurrected when we first developed ‘Pirates of the Caribbean’ for the screen a decade ago. There’s a reason why people have relished these characters and genres for decades, and we knew that if we re- introduced them in a fresh and exciting way, they would fall in love with them all over again.”

Verbinski was interested in directing “The Lone Ranger” only if they could take the classic story and stand it on its ear. “I think if you’re a fan of the original TV series,” Verbinski says, “you’re going to be surprised by the movie, because everybody knows that story, and that’s not the story we’re telling. We’re telling the story from Tonto’s perspective, kind of like ‘Don Quixote,’ told from Sancho Panza’s point of view. I would say that at its core, our version is a buddy story and an action-adventure film with a lot of irony and humor and enough odd singularity to make it distinct.”

To write the fresh take on the legendary tale, the filmmakers hired the brilliant screenwriting team of Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio, who had also scribed all four of the hugely successful “Pirates of the Caribbean” movies, the first three of which were collaborations between Jerry Bruckheimer and Gore Verbinski, and Justin Haythe, who wrote “Revolutionary Road” for Sam Mendes.

Commenting on the story, producer Jerry Bruckheimer says, “This is the story of how John Reid becomes the Lone Ranger,” adds Bruckheimer, “but in the framework of a ‘dramedy’ between two characters from totally different backgrounds, who are really at odds at the beginning of the story and through the course of their relationship come to a kind of uneasy bonding. Our version has a lot of excitement, adventure, drama, comedy, spectacle and emotion. And because of Gore’s vision, it’s also huge.”

Bruckheimer was thrilled that his “Pirates” partner Gore Verbinski was onboard the “The Lone Ranger.” “Gore is an amazingly talented director, someone who encompasses it all. Sometimes you find a director who does comedy well but can’t do action, or those who can only do action,” says Bruckheimer. “Gore is one of the very few directors who can do everything — action, drama, comedy, animation — with equal brilliance. He’s highly visual and lets nothing stand in his way to create sequences that have never been seen before, and then he somehow finds a way to shoot them to maximum effect.”

Back to School… Cowboy School (2013)

The cast and background players of “The Lone Ranger” discovered that if you want to be a cowboy, gunslinger, or railroad builder on screen, you’ve got to go back to school and be properly taught. “Cowboy Boot Camp” began three weeks before Gore Verbinski called “Action” for the first time and was attended by the vast majority of the primary cast at the Horses Unlimited ranch in Albuquerque. Their teachers included stuntmen, horse wranglers, the prop master, and armorers, and nobody was cut an easy break — not even the guy playing the film’s eponymous character.

“Cowboy Boot Camp is basically all the actors running around like six-year-old boys,” says Armie Hammer. “Riding horses for two hours a day, throwing lassos for an hour, shooting guns, riding in a wagon, putting on a saddle and taking it off. It was like an immersion project. After just a few days of boot camp, I did more riding than I cumulatively had in my entire life.”

“What Gore wanted,” explains stunt coordinator Tommy Harper, “was to have a Cowboy Boot Camp where we basically teach each actor how to shoot a gun, how to saddle and ride a horse, along with other training. This way we get to know the actors, what their abilities are, and how to keep them safe. The main thing for me is to make sure that at the end of the movie they’ve done as much as they can do safely, and end the movie being completely healthy.” Although boot camp started before filming actually began, Harper points out that the actors’ training went “all the way to the end. Just when you think you know everything, something backfires on you, so we never let them get too comfortable.”

Clearly, it was crucial for the actors to learn the correct handling of firearms, and for that they were under the expert tutelage of armorer Harry Lu. “Even though they’re shooting blanks,” notes Harper, “it’s still a dangerous piece of equipment that they’re working with, and we have to make sure that they know every bit of handling and how to look correct doing it.”

William Fichtner, who as ultimate badass outlaw Butch Cavendish had to feel absolutely secure with his weaponry, was glad to put himself in the safe hands of the experts. “With Mr. Harry Lu around, I’m comfortable with anything when it comes to firearms,” says the actor. “It’s hard… the first time you hold that heavy gun in your hand. But every time I would arrive on set and see Harry, I would ask him if I could handle the gun for a little bit, and he would always show me something new to practice, then show me a little more.” After a time, Fichtner was doing dangerously cool flips and twirls with the gun, which were captured on film during shooting in Creede, Colorado. “You know why you try so hard with things like that?” asks Fichtner. “Because as an actor, you want little moments to equal everything else that’s happening on this film. I wanted that gun move to be as good as the amazing backdrop and set we were shooting on in Creede.”

Schooling the talent on horsemanship was the film’s crack wrangling team under the supervision of head horse wrangler Clay M. Lilley and wrangler gang boss Norman Mull. “A horseman can look at an actor and know that person can’t ride a horse,” says Harper. “You can just tell by how they walk up to it, or how they mount and dismount. So teaching them how to look correct was really important.” Adds Norman Mull, “What we’re trying to do in boot camp is to get the actors comfortable with horses, pick horses for them, and teach them whatever we need to make sure they can ride. Some of the actors had some previous experience, including Armie Hammer and Ruth Wilson. “I’ve fallen off a few horses before,” says Wilson with a laugh, “so I thought this was a good place to start learning properly.” Wilson enjoyed being the only woman at boot camp. “Yeah, I loved it, surrounded by cowboys, it was quite fun. It was a really nice way of understanding the world of the movie.”

The normally fearless Hammer, however, was actually a little nervous. “I’d been on horses before, but I thought, ‘This animal thinks for itself, and that makes me a little nervous. What is it going to do if it sees a bunny?’ But they don’t give you a choice; they just stick you on a horse and say, ‘Go ride.’ It was nonstop fun for three weeks.”

The other principal actors also had a blast at boot camp, although they acknowledged the rigors involved. James Badge Dale, the New Yorker who plays tough Texas Ranger Dan Reid in the film, had to come clean about his riding skills when he first met with Jerry Bruckheimer and Gore Verbinski. “I didn’t have the job yet, and I met with the two of them. Jerry was just sitting quietly, as he often does, observing and listening carefully. Gore asked me if I knew how to ride a horse. I went back and forth with some story, and finally said, ‘Gore, I’m sorry, I have no idea how to ride a horse. I’m from New York City!’ Then Jerry suddenly starts laughing, and said, ‘You’re the first person who’s come in here and told us the truth!’ Then Gore added, ‘Well, you’re going to learn.’ And I did. I learned things about horses that I never thought I would. These wranglers are very good at what they do. They love their horses and they teach you to respect them.”

Also making an important contribution to boot camp was Kris Peck’s prop department, since it was responsible for providing the period-correct tack for the actors’ horses. They custom-made upwards of 80 Western saddles, 25 U.S. Cavalry saddles and 30 Native American saddles. “We have to teach the actors how to take off all their props and look as if they know what they’re doing,” explains assistant prop master Curtis Akin. “They have all kinds of stuff that they’re going to use for the camp scenes, so when they ride up they’re going to get off their horses, pull all this stuff out, lay their saddles around the campfire, and lay their bedrolls out to make camp for the night.”

The Lone Ranger (2013)

Directed by: Gore Verbinski

Starring: Johnny Depp, Armie Hammer, Tom Wilkinson, William Fichtner, Barry Pepper, James Badge Dale, Ruth Wilson, Helena Bonham Carter

Screenplay by: Ted Elliott, Terry Rossio, Justin Haythe

Production Design by: Jess Gonchor, Mark ‘Crash’ McCreery

Cinematography by: Bojan Bazelli

Film Editing by: James Haygood, Craig Wood

Costume Design by: Penny Rose

Set Decoration by: Cheryl Carasik

Music by: Hans Zimmer

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for sequences of intense action and violence, and some suggestive material.

Studio: Walt Disney Pictures

Release Date: July 2, 2013

Visits: 79