Taglines: Love has no borders.

A passionate love story between two people of different backgrounds and temperaments, who are fatefully mismatched and yet condemned to each other. Set against the background of the Cold War in the 1950s in Poland, Berlin, Yugoslavia and Paris, the film depicts an impossible love story in impossible times.

Cold War (Polish: Zimna wojna) is a 2018 historical period drama film directed by Paweł Pawlikowski. The film, set in Poland and France during the Cold War from the late 1940s until the 1960s, tells the story of a musical director (Tomasz Kot) who discovers a young singer (Joanna Kulig), and follows their subsequent love story over the years. The film is loosely inspired by the lives of Pawlikowski’s parents.

Cold War received universal acclaim from critics. It competed for the Palme d’Or at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival, where Pawlikowski won the award for Best Director. It also received the Golden Lions Award at the 43rd Gdynia Film Festival, five 2018 European Film Awards, and was selected as the Polish entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 91st Academy Awards, making the December shortlist. At the 72nd British Academy Film Awards the film earned four nominations, including Best Direction and Best Film Not in the English Language.

“The story of a couple like this has been with me for ages,” director Pawel Pawlikowski told Deadline. “I dedicated it to my parents, because it’s somewhat inspired by their tempestuous relationship—they had [both] a great love and a great war. Their separations, betrayals, getting together again, moving countries, changing partners, getting together again—that story has always been in the back of my head, as a kind of a matrix of all love stories. So I knew I had to do it.”

Film Review for Cold War

Love in a Communist Climate.

Paweł Pawlikowski won the best director award at Cannes in May for this sweepingly intimate love story about a star-crossed couple falling together and apart, through the iron curtain of postwar Europe. It is inspired by (and dedicated to) his parents, whom Pawlikowski has described as “the most interesting dramatic characters I’ve ever come across … both strong, wonderful people, but as a couple a never-ending disaster”.

Yet while screen lovers Wiktor and Zula share names and character traits with the film-maker’s mother and father, their individual narratives are fictional and allusive, taking us from the countryside of Poland to the streets of East Berlin, from Paris to Yugoslavia, over 15 turbulent years – crossing boundaries that are musical, geographical, political and ultimately existential. The result is a swooning, searing Polish-British-French co-production that unexpectedly put me in mind of Casablanca or La La Land as reimagined by Andrzej Wajda or Agnieszka Holland – a reminder of the fundamental things that apply, as time goes by.

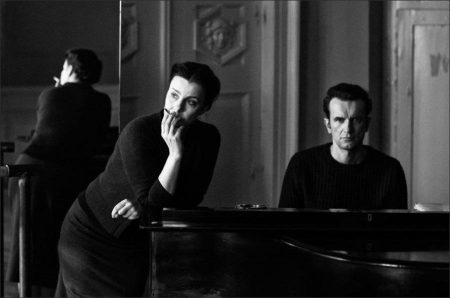

There’s a sustained tension that perfectly matches the film’s twin themes of freedom and incarceration. We open in rural Poland, 1949, where Wiktor (Tomasz Kot) and Irena (Agata Kulesza) are recording folk songs – mournful tales of love, drink and hardship, raw and elemental. Under the banner of the “Mazurek ensemble” (inspired by the real-life Mazowsze troupe), they audition musicians and dancers to showcase the authentic sounds of Poland, ensuring that “No more will the art of the people go to waste!”

Into these auditions comes Zula (Joanna Kulig), an enigmatic young woman posing as a village girl who significantly performs not a Polish mountain tune but a song learned from a Russian movie. Irena detects “a bit of a con” but Wiktor is smitten by Zula, who is whispered to have killed her father (“He mistook me for my mother, so I used a knife to show him the difference”). Soon Zula is one of the stars of Mazurek, unfazed by the authorities’ co-opting demands that they sing the praises of Stalin and agricultural reform. When Wiktor spies a chance to defect during a 1952 engagement in East Berlin, he begs Zula to come with him. But are her pragmatic priorities in sync with his western-leaning dreams?

Returning to the Academy-ratio black-and-white format of the Oscar-winning Ida, Pawlikowski and cinematographer Łukasz Żal’s stunning images evolve from the carefully composed static frames of yore to more free-form movements that match the musical shifts of the tale. Just as the Mazowsze folk favourite Dwa serduszka (Two Hearts) mutates from a rural tune to a jazzy ballad.

So Pawlikowski subtly negotiates a series of aesthetic key changes, mirroring the ebb and flow of this tumultuous love story. There’s a sustained tension between the concisely epic sweep of the narrative and boxy confinement of the 4×3 frame that perfectly matches the film’s twin themes of freedom and incarceration. A scene in which Zula dances drunkenly to the sounds of Bill Haley’s Rock Around the Clock vibrantly captures that sense of liberation and entrapment intertwined.

At the heart of it all is Kulig, who previously worked with Pawlikowski on The Woman in the Fifth and Ida, and who here delivers a star-making performance of astonishing range and depth. Before our eyes we see Zula transform from not-so-innocent young woman (she candidly confesses to spying on Wiktor for state security) to sultry jazz singer and raddled showgirl; from faux “pure Polish” belle to smoky Parisian chanteuse; from victim to victor and back again.

Since Cold War’s rapturous debut at Cannes, Kulig has been widely compared to Jeanne Moreau, although her intelligence and tough sensuality reminded me more of Léa Seydoux; like her, Kulig could doubtless slip with ease between accomplished artist actor and badass Bond girl. Coincidentally, Kulig’s co-star, Tomasz Kot, was reportedly Danny Boyle’s choice for the next Bond villain – a possible source of the “creative conflicts” that led to Boyle’s recent departure from that forthcoming film.

Plaudits, too, to musician Marcin Masecki, a key collaborator who Pawlikowski originally considered for the role of Wiktor, and who is credited with the “jazz and song arrangements”. Just as Miles Davis pointed out that “It’s not the notes you play, it’s the notes you don’t play” that matter, Cold War is a dark musical full of silences and ellipses. It’s up to the audience to fill in the episodic gaps in the narrative, and to divine the true feelings that so often remain unspoken. Appropriately, it left me speechless.

… we’re asking readers to make a new year contribution in support of The Guardian’s independent journalism. More people are reading our independent, investigative reporting than ever but advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. And unlike many news organisations, we haven’t put up a paywall – we want to keep our reporting as open as we can. So you can see why we need to ask for your help.

The Guardian is editorially independent, meaning we set our own agenda. Our journalism is free from commercial bias and not influenced by billionaire owners, politicians or shareholders. No one edits our editor. No one steers our opinion. This is important as it enables us to give a voice to those less heard, challenge the powerful and hold them to account. It’s what makes us different to so many others in the media, at a time when factual, honest reporting is critical.

Cold War (2018)

Directed by: Pawel Pawlikowski

Starring: Joanna Kulig, Tomasz Kot, Borys Szyc, Agata Kulesza, Janusz Glowacki, Piotr Borkowski, Aloïse Sauvage, Jeanne Balibar, Adam Woronowicz, Anna Zagórska, Izabela Andrzejak

Screenplay by: Pawel Pawlikowski

Production Design by: Benoît Barouh, Marcel Slawinski, Katarzyna Sobanska-Strzalkowska

Cinematography by: Lukasz Zal

Film Editing by: Jaroslaw Kaminski

Costume Design by: Ola Staszko

Set Decoration by: Marcel Slawinski, Katarzyna Sobanska-Strzalkowska

Music by: Marcin Masecki

MPAA Rating: R for some sexual content, nudity and language.

Distributed by: Kino Świat

Release Date: June 8, 2018 (Poland), August 31, 2018 (United Kingdom), October 24, 2018 (France)

Visits: 118