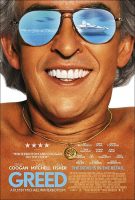

Taglines: The devil is in the retail.

Introducing Greed, Michael Winterbottom’s comic portrait of an epically avaricious and self-adoring fashion tycoon, which centers on his lavish 60th birthday celebration, the director admitted he’d been inspired by some actual figures’ excesses, and “in the real world they’re even more absurd.”

Well, of course they are. Compared to many well-publicized indulgences of the One Percent, nothing here really even registers as satire — not the party staff dressed in togas, not the live lion rented to pantomime a gladiator fight, not the suggestion that famous guests are being paid to attend.

Though frequently chuckle-worthy, this party is tame stuff, however offensive, and not the film’s most revealing vantage point on the fast-fashion huckster played with brio by Steve Coogan. Structured a bit like Citizen Kane hot-glued to the front of an Altman ensemble shamble, it’s a wobbly but amusing pic that only really raises eyebrows at the end, when it briefly behaves like a cry for global economic justice.

Coogan’s Sir Richard McCreadie, known as “McGreedy” or “Sir Shifty” in the tabloids, has had a long career of buying up clothing stores, driving them into the ground and somehow getting rich in the process. It’s a career merging cutthroat psychological acumen — don’t try negotiating prices with this guy — with a tragic insistence that underlings obey his every whim.

The movie’s most involving sequences reach back into the lore of his ascendance, both in one-on-one haggling and, later, in a Big Short-style interview where a financial journalist (Paul Higgins) explains shenanigans involving real estate and Escher-like loan arrangements.

This is promising stuff, in which a fictional mogul’s childhood class resentment drives him to build an empire and whisk the money away to Monaco, where no one can tax it. There, Richard’s wife Samantha (Isla Fisher) happily received a 1.2 billion-pound “dividend” and spent a bit of it on a megayacht she designed herself.

But the film’s framing event, which takes over in the second half, eschews such focus. By this point in his life, Richard and Samantha are amicably split, behaving like old mates while each brings a hot new lover to Mykonos, the site of their five-day celebration. They arrive well before things are ready, and the not-ready-ness is milked for a good deal of agitated conversation. There are Syrian refugees camped on the beach, spoiling the view; bad press has caused many celebs to back out of plans to attend; and the plywood-and-paint faux Colosseum Richard insists on is far from completion.

A small galaxy of underdeveloped characters hovers here, from the McCreadie’s privileged kids (a resentful son, a largely invisible son and a daughter whose participation in a reality show could easily have been cut from the film) to their employees and a few locals. David Mitchell’s Nick, a well-read journalist with an inferiority complex, gets the most screen time as the man writing Richard’s official biography. Having interviewed old colleagues and visited the Sri Lanka textile factories Richard does business with, he’s now hovering on Mykonos for fly-on-the-wall material.

A high-level McCreadie staffer named Amanda (Dinita Gohil), who at first seems meant to be Nick’s love interest, does a job for Richard that is explained fleetingly if it’s mentioned at all. As Nick befriends her, we learn that she has family back in one of those Sri Lankan factories; she hopes that, in his inept video documentation of his travels there, Nick caught a shot or two of her aunt.

As the two keep bumping into each other, viewers may suspect Winterbottom and co-writer Sean Gray have something clever up their sleeves: Maybe Nick is secretly assembling an exposé, and Amanda’s insight into worker exploitation is the last puzzle piece he needs? But if such a thought ever entered the filmmakers’ heads, it was dropped along the way.

With the arguable exception of Nick, none of the supporting characters gets enough love from the film to generate the kind of group sociological portrait Greed seems to intend. We don’t get subplots so much as bits of business with occasional laughter — certainly nothing interesting enough to justify the weight this party gets in the portrait of a rapacious capitalist. A dark turn toward the end holds some satisfactions but doesn’t really feel earned, while real-world statistics placed over the credits (which call out, among other things, unnamed “celebrities” who endorse exploitative fashion brands) have more bite than anything else in this easy critique.

Greed is an 2019 British satirical film, written and directed by Michael Winterbottom. The film stars Steve Coogan, David Mitchell, Isla Fisher, Shirley Henderson, Asa Butterfield, Dinita Gohil, Shanina Shaik and Sarah Solemani. Greed had its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival on 7 September 2019, and is scheduled to be released in the United Kingdom on 21 February 2020, by Sony Pictures Releasing.

Greed (2020)

Directed by: Michael Winterbottom

Starring: Asa Butterfield, Sophie Cookson, Isla Fisher, Shirley Henderson, Steve Coogan, Stephen Fry, Sarah Solemani, Jamie Blackley, Pearl Mackie, David Mitchell, Shanina Shaik

Screenplay by: Michael Winterbottom

Production Design by: Denis Schnegg

Cinematography by: Giles Nuttgens

Film Editing by: Liam Hendrix Heath

Costume Design by: Anthony Unwin

Art Direction by: Matt Fraser

Music by: Harry Escott

MPAA Rating: R for pervasive language and brief drug use.

Distributed by: Sony Pictures Releasing

Release Date: February 21, 2020 (United Kingdom)