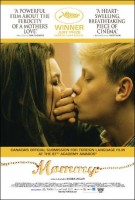

Mommy Movie Storyline. Forty-six year old Diane Després – “Die” – has been widowed for three years. Considered white trash by many, Die does whatever she needs, including strutting her body in front of male employers who will look, to make an honest living. That bread-winning ability is affected when she makes the decision to remove her only offspring, fifteen year old Steve Després, from her previously imposed institutionalization, one step below juvenile detention.

She institutionalized him shortly following her husband’s death due to Steve’s attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and his violent outbursts. He was just kicked out of the latest in a long line of facilities for setting fire to the cafeteria, in turn injuring another boy. She made this decision to deinstitutionalize him as she didn’t like the alternative, sending him into more restrictive juvenile detention from which he would probably never be rehabilitated. However, with this deinstitutionalization, she has to take care of him.

Director’s Note

Since my first film, I’ve talked a lot about love. I’ve talked about teenage hood, sequestration and transsexualism. I’ve talked about Jackson Pollock and the 90s, about alienation and homophobia. Boarding schools and the very French- Canadian word “special”, milking the cows, Stendhal’s crystallization and the Stockholm syndrome. I’ve talked some pretty salty slang and I’ve talked dirty too. I’ve talked in English, every once in a while, and I’ve talked through my hat one too many times.

Cause that’s the thing when you “talk” about things, I guess, is that there is always this almost unavoidable risk of talking shit. Which is why I always decided to stick to what I knew, or what was -more or less – close to my skin. Subjects I thought I thoroughly or sufficiently knew because I knew my own difference or the suburb I was brought up in. Or because I knew how vast my fear of others was, and still is. Because I knew the lies we tell ourselves when we live in secret, or the useless love we stubbornly give to time thieves. These are things I’ve come close enough to to actually want to talk about them.

But should there be one, just one subject I’d know more than any other, one that would unconditionally inspire me, and that I love above all, it certainly would be my mother. And when I say my mother, I think I mean THE mother at large, the figure she represents.

Because it’s her I always come back to. It’s her I want to see winning the battle, her I want to invent problems to so she can have the credit of solving them all, her through whom I ask myself questions, her I want to hear shout out loud when we didn’t say a thing. It’s her I want to be right when we were wrong, it’s her, no matter what, who’ll have the last word.

Back in the days of I Killed My Mother, I felt like I wanted to punish my mom. Only five years have passed ever since, and I believe that, through Mommy, I’m now seeking her revenge. Don’t ask.

Visuals

We saw Mommy as a dark movie in its core, but we thought that, on the outside, it should be polished with light and warmth. It’s the audience’s mandate to identify the true nature of the film, not ours. From our end of things, we wished not to tell anyone what to think, or when to think it.

Bathing Mommy in whatever predictable grey, damp fog therefore seemed like cheap automatism. I dreamed of a joyful place for Die and Steve to live in, a place where everything was possible. I remember swearing to myself that I’d do everything so my characters would look and sound like the actual people from the suburb I was brought up in. Not just some caricature of themselves, but “themselves”, truly.

The movie’s photography had to avoid the usual tropes of despondency too. The sunsets and the magic hours, during which many sequences would take place, would drape the exteriors with reds and yellows, and the broad, harsh daylight would even blind us with its almost jovial flares.

To me, it was crucial for Mommy, by all possible means, to be a radiant tale of courage, love and friendship.

I don’t see the point in making films about losers, nor the point in watching them. Which doesn’t have anything to do with a contemptuous standpoint towards “losers” – on the contrary. I just have a particular aversion to any artistic document purporting to portray human beings through their failures. Human beings who, I think, shouldn’t be defined by hardships and tags, but by feelings and dreams. Which is why I wanted to make a movie about winners, whatever befalls them in the end. I truly hope I have at least achieved that.

The Cast

As always, I wanted the actors to be at the center of everything. I have an endless fascination for them, and studying the art of acting, investigating all of its forms and styles, analyzing its structure, refining it, understanding it is my ultimate goal.

This time around, I was hoping to take the cast along a somewhat less “latin”, less exuberant path than that of Laurence Anyways, and a less cerebral one than Heartbeats.

Mommy’s characters aren’t playing games, and don’t know how to express their feelings with the immodest ease with which many of my previous characters have. Die, Steve and Kyla aren’t show-offs. But they are highly boisterous, colourful beings capable of getting their point across in a coherent fashion regarding their respective background and situation.

For me, working with Anne Dorval and Suzanne Clement again was not about returning to old patterns, but trying new ones. It was one of the most exciting – and obvious – challenges of the movie; that one shouldn’t “recognize” them. As for Antoine, he was the surprise, of course. Any filmmaker is proud to reveal new talent, or confirm talent that already has been. To me, it’s both a passion and a purpose — working with great artists and, with them, creating great performances and trying to trigger great emotion.

I feel like somewhere in time, our love of true, precise characters has withered and been replaced by ready-to-wear roles, to the benefit of whatever efficiency. We confiscate their surnames, their story, theirs tics, their guilty pleasures, their “details”. We ship actors off in labeled boxes, as long as they fit in the great grid of intelligible, rentable storytelling. But interesting human beings – at least the heroes of my childhood – have always existed in a far more concrete way, and the actors I admire, and with which I love to work, always put the concrete reality they’ve known and observed forever to the service of a movie. And to me, that’s always been what’s typical of great actors — they create characters, not performances.

Mommy vs. I Killed My Mommy

There are several parallel lines to be drawn between my first movie and Mommy. But only on the surface. As far as I’m concerned, from direction to tone, acting style to visuals, those two films are two different planets. One unfolds through the eyes of a whimsical teenager, the other contemplates a mother’s hardships. Apart from the already important switch of point of view, here is why I think those two films are intrinsically dissimilar — I Killed My Mother centres on a puberty crisis, Mommy, on an existential one.

Moreover, there is no point for me to make the same film twice. I’m delighted by this opportunity of homecoming through these mother-and-son dynamics, as that theme has always been a part of my films. But I’m all the more delighted by the opportunity to not only attempt to explore novelty within my own filmography, but to try exploring novelty on an even larger scale, that of the family movie genre. Because it represents the most emotive form of communication with the audience.

The mother is where we’re from, and the child, who we are, who we’ve become. We never are truly at rest with those Freudian preoccupations, and they’re an indelible part of us.

Music

I think music in film achieves an unconscious transaction with each and every individual in an audience, spurring them on to engage in the film throughout their own story. Dido, Sarah McLachlan, Andrea Bocelli, Celine Dion or Oasis all have a history with each cinephile; when Wonderwall, for instance, was playing in 1995, one of them was heartbroken while the other was alone in some bar, or on honeymoon in Playa Del Carmen, or on her or his way back from a friend’s funeral. When triggered by the sound of music, those private memories can then open and the film’s writing suddenly goes farther than we thought it would. In the still of a dark theatre, we watch, in an anonymous togetherness, and I think that’s undeniably profitable for any movie.

Besides, the notion that almost every song playing in Mommy comes from a mixtape Die’s husband made before he died, and not from my own personal playlist, was a new thing for me in terms of cinematic system. I remember Pauline Kael writing about Scorsese and saying that, in the type of movies he made, songs weren’t playing ON movies anymore, but IN movies; on the radio, on tv, or in cafes. There is, in this diegetic approach, a way of engaging the public in the authentic, naked truth of the characters, making them forget about a director’s ideas and desires. I like that.

Mommy

Directed by: Xavier Dolan

Starring: Anne Dorval, Antoine-Olivier Pilon, Suzanne Clément, Patrick Huard, Alexandre Goyette, Michèle Lituac, Viviane Pascal, Natalie Hamel-Roy

Screenplay by: Xavier Dolan

Cinematography by: André Turpin

Film Editing by: Xavier Dolan

Costume Design by: Xavier Dolan

Set decoration by: Jean-Charles Claveau

Music by: Nola

MPAA Rating: R for language throughout, sexual references and some violence.

Studio: Roadside Attractions

Release Date: January 23, 2015

Views: 139