Taglines: Are you tTired of the expected?

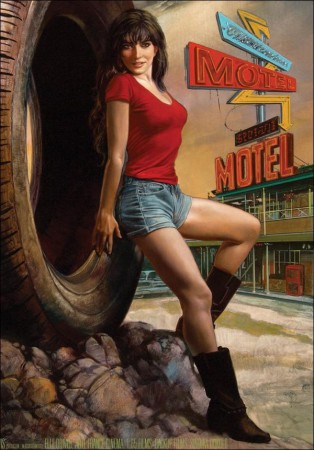

Rubber is the story of Robert, an inanimate tire that has been abandoned in the desert, and suddenly and inexplicably comes to life. As Robert roams the bleak landscape, he discovers that he possesses terrifying telepathic powers that give him the ability to destroy anything he wishes without having to move.

At first content to prey on small desert creatures and various discarded objects, his attention soon turns to humans, especially a beautiful and mysterious woman who crosses his path. Leaving a swath of destruction across the desert landscape, Robert becomes a chaotic force to be reckoned with, and truly a movie villain for the ages.

Written and directed by legendary electro musician Quentin Dupieux (Steak, Nonfilm), aka Mr. Oizo, Rubber is a smart, funny and wholly original tribute to the cinematic concept of “no reason.”

About the Production

In March of 2009, Quentin Dupieux and Realitism Films decided to take on a technological and aesthetic challenge: to produce a film in less than a year, in English and in Los Angeles in order to take advantage of the new production and post-production technologies.

Quentin Dupieux immediately begins with the writing of the script for RUBBER. Canal +, Arte and the international sales agent Elle Driver immediately accept to participate in the adventure. In October 2009, the film crew scours the California desert and creates one of the first feature films shot entirely with a still camera. In December 2009, the crew is back and ready to start post-production. Completed in March 2010, the film was selected for the Critic’s Week at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival.

Interview with Producers

What was the starting point in terms of production?

Gregory Bernard: From the start, we decided that, to be totally free, we would make a low budget film and that would be the only constraint. No need to wait three years to make a film. To be free, you can’t be dependent on a big cast. A lot of actors would love to work with Quentin but there would have meant dealing with timing. You can make a more expensive film but that means taking the time to raise funds, to organize a casting, which means also you don’t leave much by way of loose ends and you limit the artist’s creative freedom.

Quentin is a full-fledged artist. He does everything: he writes, frames, shoots and does the editing. The film is entirely his. And if we were going to shoot a totally free film, we both wanted to take the opportunity to live an adventure that would be a perfect movie cliché: make a film in English, in L.A.

Julien Berlan: Quentin adjusted very well to that constraint. In any case, the idea was to make a film in less than a year, so he gave us the script very quickly. Going fast was what he wanted from the get go.

Is it more expensive to make a film in the United States than in France?

JB : The American movie industry is going through a severe crisis, so the circumstances were very favorable for us. Shooting in the U.S. costs less, inasmuch as you accept to fit into certain slots as defined by the system, with the advantage that different types of productions obey different sets of rules. If your project fits into what actors’ syndicate calls “low budget agreements”, for instance.

GB: We lucked out also in terms of timing, although the film was on the verge of being cancelled a few times! I had the horrible experience of having to tell Quentin we could not make the film for lack of funds. Julien and Quentin never gave up and that was enough for us to decide to go for it no matter what. Rubber came to be thanks to our indomitable desire! Julien even put in some of his own money at the last minute. Our entire confidence in Quentin gave us an energy that carried us from beginning to finish. We believed in the final result enough to take risks.

Was it easy to find funds after Steak?

GB: Steak is a cult movie, but it was not a success in terms of theatre audience compared with the promises of the distribution, so it was not so easy to go to Canal + with a new Quentin Dupieux movie. But the people at Canal quickly decided to invest a little money. They understood our urgency and that is what allowed the film the happen.

How do you persuade someone to produce a film with a tire as its main character?

GB: The people at Canal + just liked the script. They trusted us without knowing just what the film would look like, even though the result finally turns out quite close to the script. They chose to bet on it, as we did, but it was a bit of a rebellious act.

JB: The Americans also loved the script. A few big names, like Matthew Modine, were interested. The script made them laugh; they immediately accepted the absurd comedy aspect of the project. We had the same reaction when we presented the project to Arte, to Wild Bunch and to Elle Driver, who quickly got involved for international sales and helped us finance the film.

How did you meet Quentin Dupieux?

GB: I’ve known him for a while. I love the Non Film. I’ve been bugging Quentin for a long time to let me produce him because I strongly believe in his talent. And he never talks about something he’s not going to do, which creates a climate of absolute trust. What he did in the States during the shooting is astounding. The crew was immediately right behind him. Everything worked incredibly smoothly. He is great about dealing with the unexpected. He wasn’t happy with the results from night shoots, in particular the scene of the fire. So he very quickly modified the script to have nothing but day scenes.

You worked with a short crew?

JB: There were probably more people than you would imagine for this type of film. Altogether, there were about thirty people on the crew, which is relatively little compared with an American shooting where you quickly get to the hundred.

GB: Everyone did more than one thing. Everybody got their hands dirty.

Quentin Dupieux was shooting his film with a digital camera, without a cameraman, that didn’t worry you?

GB: Quite the opposite. When we decided to make the film, we immediately went and purchased the famous Canon 5D. While Julien was looking into questions of scouting for locations, we went and did some tests in Corsica at sundown, and the result was wild. Quentin understood how to take advantage of the camera right away. He was very comfortable with it. He actually has his little secrets now. Canal gave us their agreement after visualizing those tests. That’s also what happened with Elle Driver, a subsidiary of Wild Bunch.

JB: We still took quite a bit of risk. When we went ahead, we were not sure that everybody would follow us. We had to put in some personal money, which is not generally a good idea – at least that’s what they teach you in production schools.

GB: In any case, relatively to the risks, the cost of a cancellation on such a project is enormous. When we bet on the film, we were certain to have something to show, even unfinished, and even if no one had come along. It’s more gratifying anyway and you can think of it as an adventure. Now we can consider the bet is fulfilled, esthetically as well as economically.

Is it easy to get money for a budget way below average?

GB: It’s easier but it takes more time. RUBBER is not an easy film. Making the film on a 5 million euro budget would have meant dragging people into something fairly uncertain. As it is, the film has its own economical logic.

JB: With the idea of making a film within a year, the budget had to remain fairly low anyway.

GB: And the main objective was also to be free. The more expensive it gets, the less freedom you have. Which is natural. If people invest a lot, they want you to be accountable. On a small budget, investors tend to be more adventurous. The other advantage when you make a film with little money is that you never have time to get bored. Quentin defines the frame he wants and in 5 minutes everything is ready.

Still, did you sometimes have cause for anguish?

GB: Yes. The day before shooting, we realized the tire didn’t work. We had to reorganize the shooting schedule and in a few days we managed to build a new remote-controlled tire with the help of a local do-it-yourself enthusiast! In the end, what we got is better than we hoped for. We did everything thanks to Quentin’s intelligence and the tenaciousness of a local special effects company boss.

All in all, you both say the same thing about the virtues of the handcrafted aspect of Quentin Dupieux’ film, on an artistic as well as an economic level.

GB: I personally really enjoy such work conditions. And I’m not going to complain that he spends too little! In fact, he liked working with that digital camera so much he will have a hard time going back to his old ways.

JB: All the more since, once kinescoped into 35mm, the result is outstanding. And it’s so easy to use, the artist can get all due credit.

GB: Making films produced with 1 million euros, with minimal waiting time between the first spark and the finished product is an ideal situation. It forces us to be free and incites others to get into the groove with us. Which is impossible with a big budget. It’s wonderful to have this type of relationship with our partners. We can get a machine going and hope others will come and hop in with us.

Could you have done all that a few years ago?

JB: Probably, but not with the same amazing image quality. The revolution is also that we are getting closer to the excellence of 35mm. On the other hand, this type of production requires all sorts of concessions from the director. No cameraman, for instance. Not everybody can do what Quentin does: take care of the script, the photography, the music, etc.

GB: That’s what’s interesting about the venture. Quentin will probably lose some people along the way, because he is never demonstrative, doesn’t tell you what you must feel at a particular moment with a little music saying you should laugh or be scared. His vision is absolutely free, it is at once controlled and instinctive, that’s what he stands for, and that gives the spectator great freedom. The response won’t be unanimous. We don’t know how the public will react or how the professionals will react. As with music, we have a feeling people are regaining a certain power and autonomy.

They also want something where they are not as passive, where contemplating a film requires some delicious effort on their part. In Wall-E, as in most films where an object comes alive, the spectator is systematically taken by the hand with the music, the expressions in the eyes, the editing, and the direction. Quentin is always aware and he avoids this sort of complacency. The spectator feels a little abandoned, he doesn’t know where he is. That will be the main criticism. And yet it is probably Rubber’s greatest asset. The spectator will be contaminated with the film’s freedom. The struggle is on the screen but it is also in the theatre. A guerillero spirit I hope we can perpetuate in films to come.

Rubber

Directed by: Quentin Dupieux

Starring: Stephen Spinella, Roxane Mesquida, Jack Plotnick, Wings Hauser, Ethan Cohn, Hayley Holmes, Haley Ramm, Cecelia Antoinette, Tara Jean O’Brien

Screenplay by: Quentin Dupieux

Cinematography by: Quentin Dupieux

Film Editing by: Quentin Dupieux

Costume Design by: Jamie Redwood

Art Direction by: Zach Bangma

Music by: Gaspard Augé, Quentin Dupieux

MPAA Rating: R for some violent images and language.

Studio: Magnolia Pictures

Release Date: April 1, 2011

Hits: 140